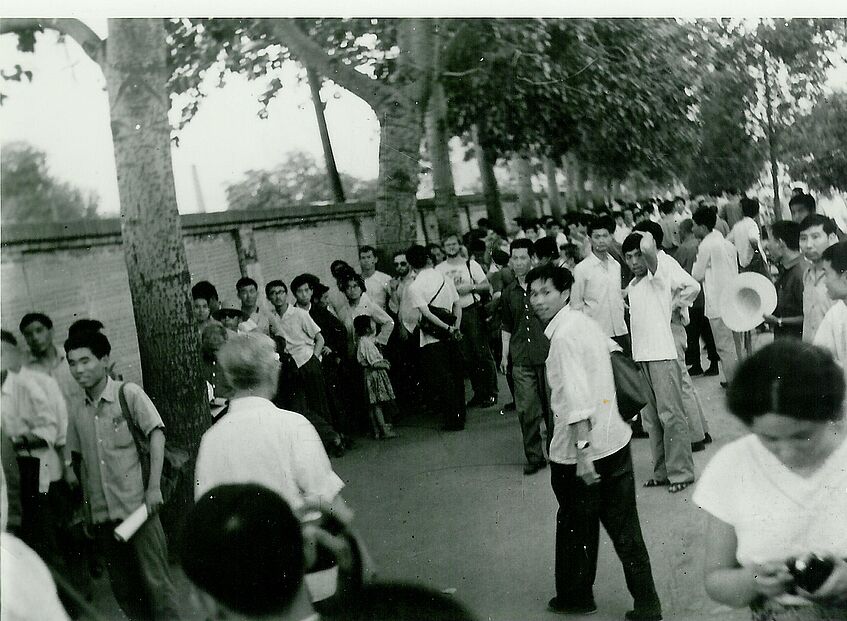

The "Xidan Democracy Wall"

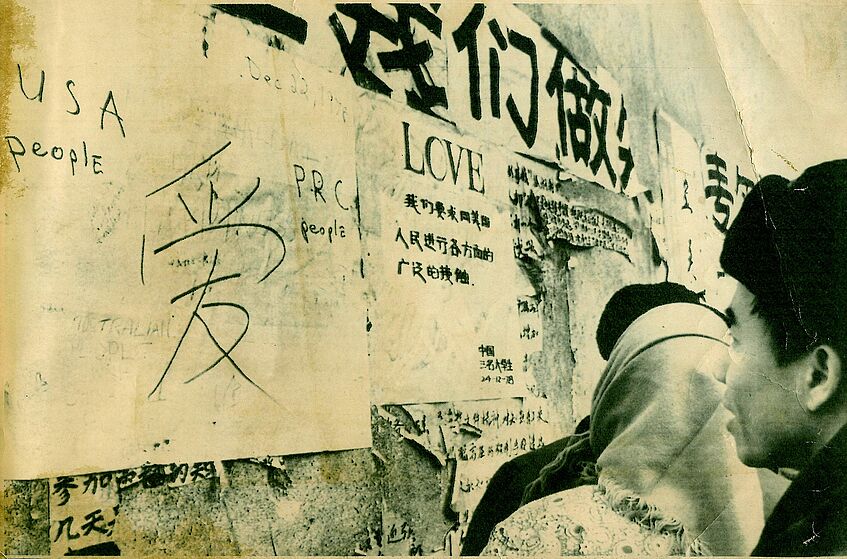

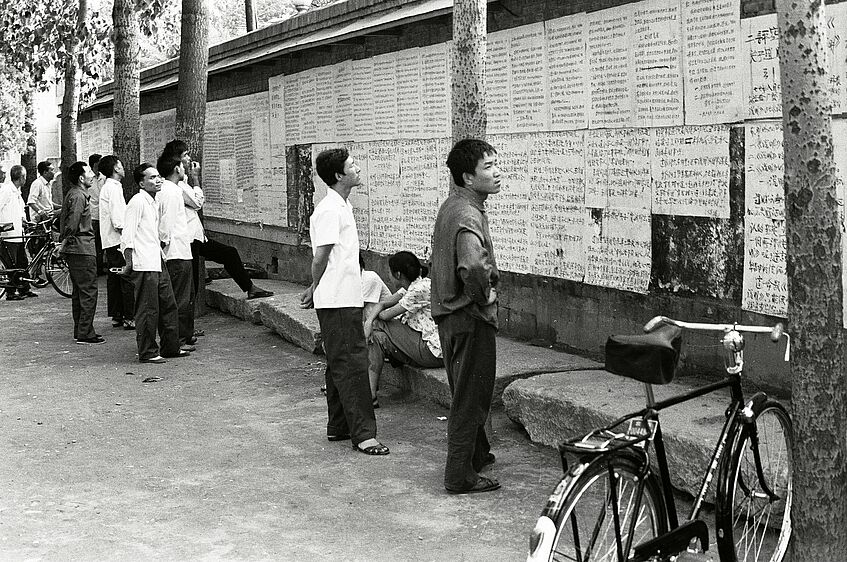

"Democracy Wall", Beijing, June 1979 (with the author Helmut Opletal, wearing a printed T-shirt)

Dazibao (大字报) – "Big-Character Newspapers"

They are a very Chinese phenomenon, these big sheets of paper manually inscribed with texts and slogans, to be displayed in public places in order to reach interested readers. Dazibao may serve for official or personal announcement, commercial advertising or political propaganda, but they may also be used for debates or public criticism.

Mao Zedong traces them back to times when Chinese characters were first used 3000 years ago, in modern China this phenomenon is initially observed during the Xinhai Revolution of 1911. But these "big-character posters" (as dazibao tend to be called in English) have gained greater importance only in the political campaigns of Chinese communists in the 1950s.

As early as 1957, but more so during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) official texts praised the "four big (freedoms)" (四大), i.e. "to speak out freely, air views fully, hold great debates and write big-character posters". These "freedoms" were not to be taken literally in a Western sense. Dazibao at that time mainly served to denounce ostracized individuals and politicians or declare allegiance to the Communist Party and its leaders. Red Guard posters in the late 60s vied with one another in adulation for the "Great Leader", and sometimes Mao himself drafted a dazibao like the famous "Bombard the Headquarters" from August 1966 that initiated the hot and violent phase of the Cultural Revolution.

During periods of change and conflict in China, big-character posters were sometimes a "permitted" or at least tolerated form of expressing criticism and personal opinions about cadres in the state enterprises, working conditions or problems in daily life. They provided a means of bringing texts and opinions to a wider public that could never be carried by the strictly controlled official media.

The 1975 Constitution

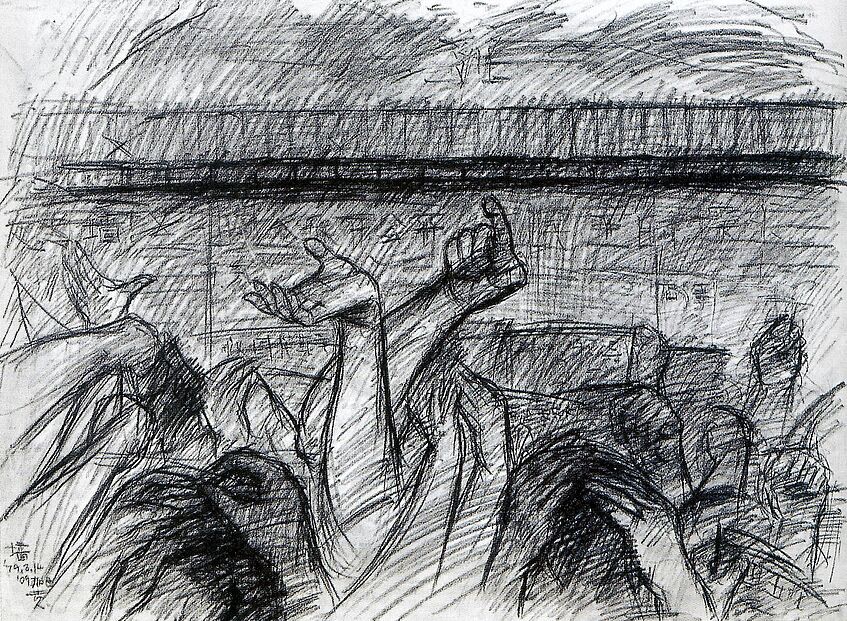

"Democracy Wall" (drawing) by Huang Rui

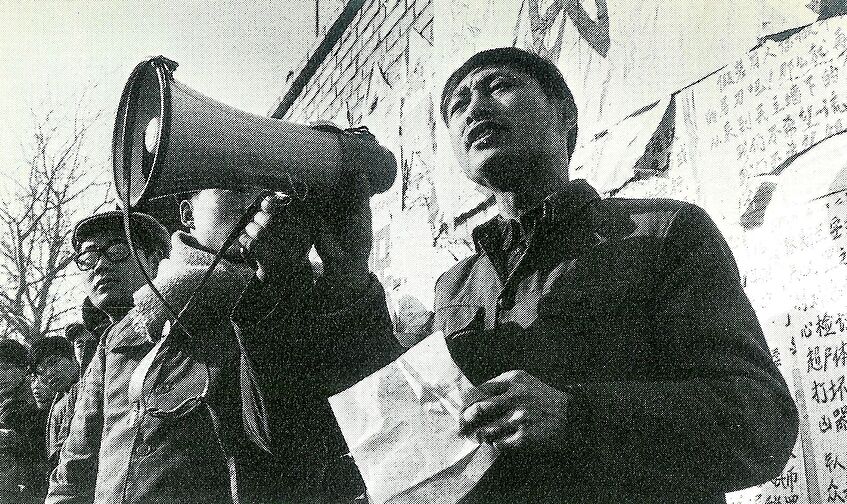

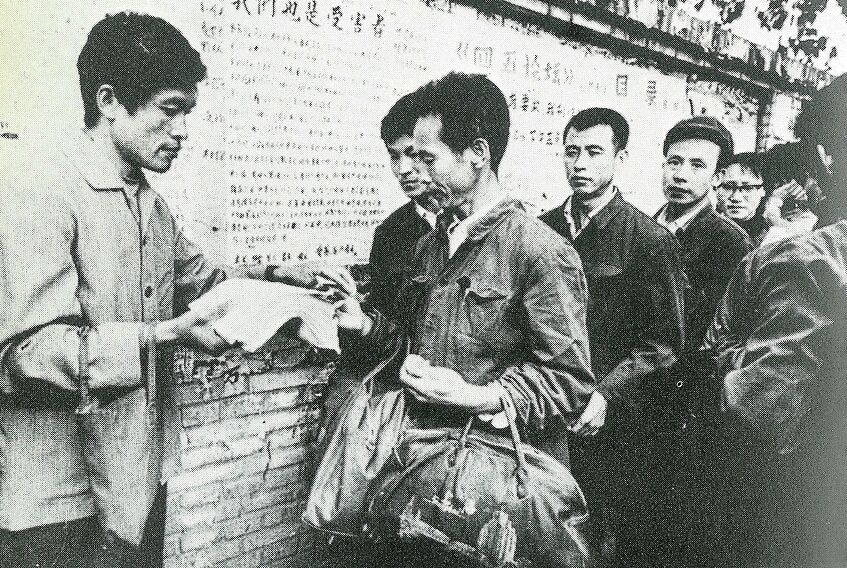

Political rally at the Democracy Wall (Liu Qing, 1979)

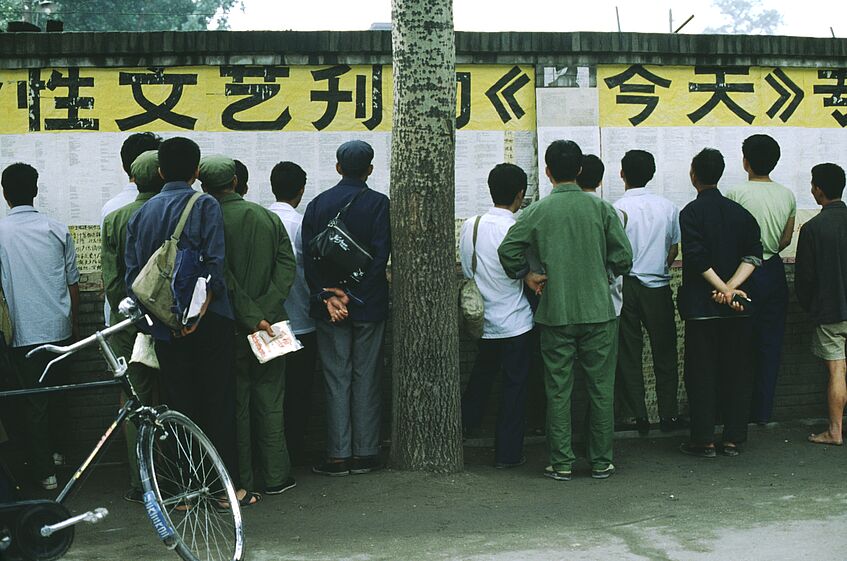

The independent cultural magazine "Today" posted at the Wall

Sale of an independent journal

The 1975 Constitution

Still in accordance with Mao's interpretations and the narratives of the Cultural Revolution, the "four big freedoms" were included in the new 1975 state constitution, and it was this clause that was regularly invoked by the authors of critical dazibao at the end of the 1970s.

When in late 1978 in Beijing and in other cities the first posters appeared that criticized the government and even Mao, that for the first time used words like "human rights" and "multi-party democray" in demanding profound political changes, this certainly was a sign that the intellectual, cultural and political elites in China were deeply worried about the future.

How far should reforms in the society go? Which ideals of the communist revolution would still be valid in the future? To which extent the teachings of the "Great Leader" Mao who had died just two years ago, had to be questioned? And were there not many ideas and beliefs from the prosperous West that could also be useful for China?

In 1978 there was still something like an ideological vacuum in China that seemed to allow all kinds of reflections and debates. Mao's successor, the new Party Chairman Hua Guofeng (华国锋), appeared weak and not very charismatic, and when Deng Xiaoping was rehabilitated in 1977 to become the most influential leader in China, Hua's influence further diminished.

But the picture was mixed, among the old communist revolutionaries there were many who had been ill-treated and attacked during the Cultural Revolution, and others who had always found a way to come to terms with the circumstances. But most of them remained faithful to the Maoist ideals, and many therefore were sceptical towards Deng Xiaoping's ideas of introducing strong market elements into the economy and liberalizing the society.

This is why at that time there were few genuine "reformers" who supported deeper political changes, and if they did, it remaind difficult for them to express and promote such ideas inside the leadership. Most likely it were some relatively young cadres such as Hu Yaobang, the former First Secretary of the Communist Youth Leage, and a number of senior journalists and cultural officials.

In 1978 and 1979 it became clear that Deng Xiaoping had the final say in most political matters, and this was also true – although in unexpected ways sometimes – for the rise, the toleration and eventually the repression of the Democracy Wall Movement and the critical posters.

At the beginning, around October 1978, there were still several places in the center of Beijing where "petitioners" and other activists' groups (like the "Enlightenment Society" from Guizhou) used to post their complaints and manifestos: around Tiananmen Square, in the Wangfujing shopping street further to the east (where the party newspaper "People's Daily" had its office), or along the main Chang'an Avenue (near the entrance to Zhongnanhai government complex occupying a part of the old Imperial Palace), and also on the university campuses in the north-western district of Haidian. A TV report by Jim Laurie for the US Network ABC illustrates the atmosphere around the newly established Democracy Wall at the end of 1978. French sinologist Alain Peyraube has filmed scenes of crowds watching big-character posters at the Democracy Wall during the last week of December 1978. Another video by Helmut Opletal was produced in late June 1979. More photos of big-character posters at the Xidan Democracy Wall (1979) and at the Yuetan Park (1980) you may view here.

The Xidan Democracy Wall

Thousands of people gather after work and at weekends in front of the Democracy Wall.

Open-air exhibition by artist Xue Mingde (薛明德)

"Love between China and the US"

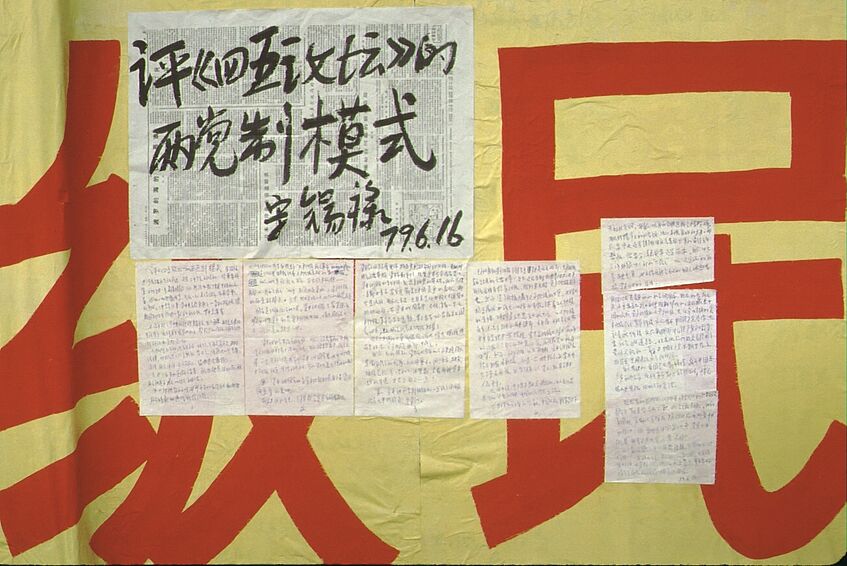

Commentary on an article by the "April 5th Forum" suggesting a two party system.

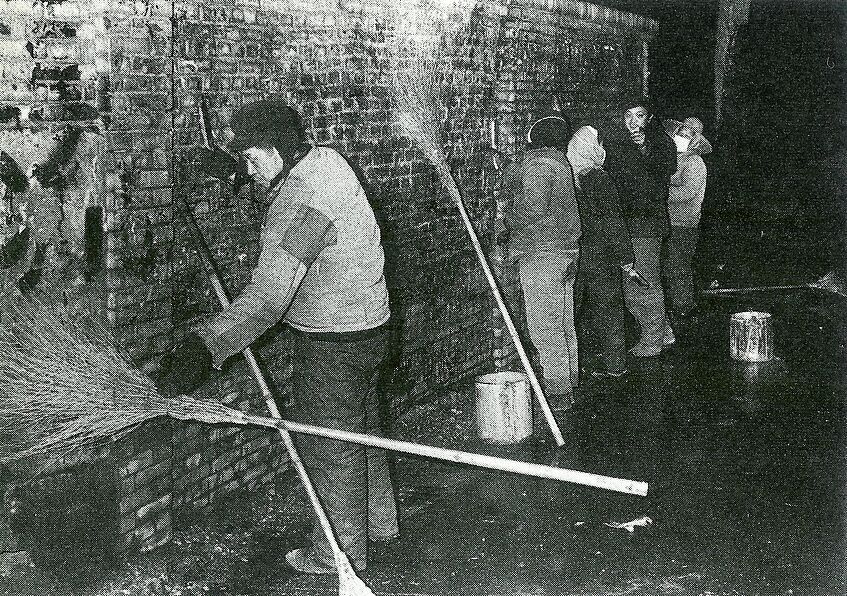

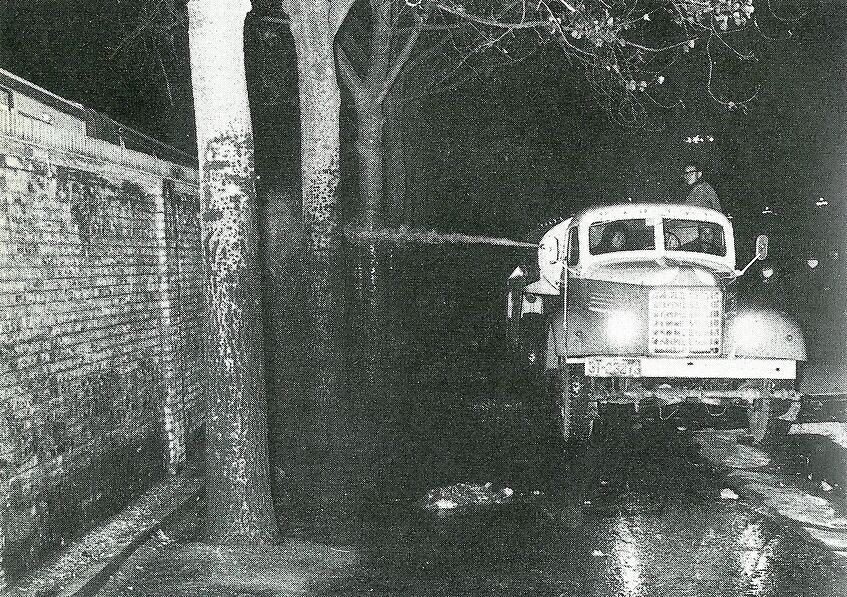

During the night from December 6 to 7 Bejing authorities send their cleaning brigades.

The last traces of posters are removed from the Xidan Democracy Wall.

Only few people show interest in the posters at the more isolated Yuetan Park.

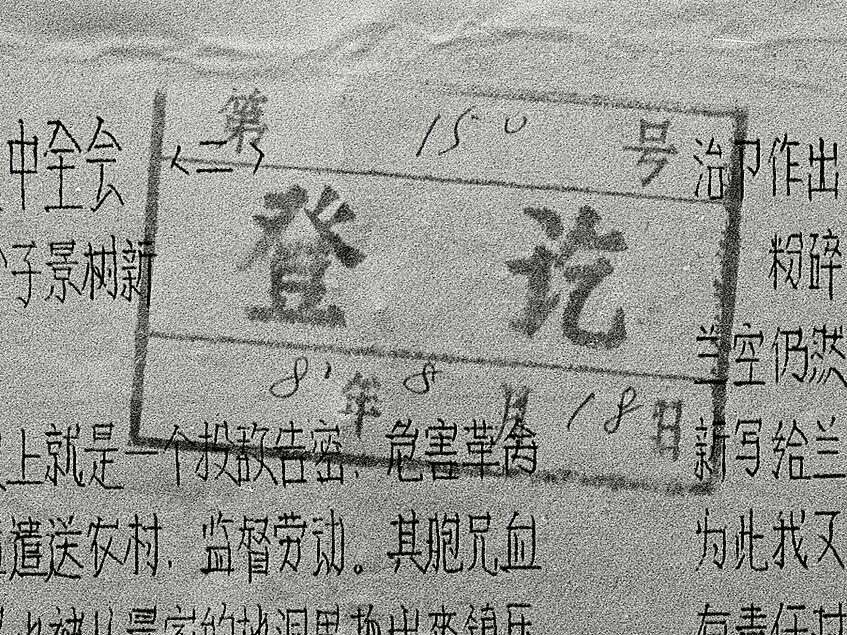

"Registration Office for Big-Character Posters"

All texts have to carry an approval stamp.

The Xidan Democracy Wall

It was the end of November 1978 when the 200 Yards long brick wall a mile and a half to the west of Tiananmen Square becomes the focal point of big-character Posters and other independent political activities.

The wall deliminates a bus terminal adjacent to the busy Xidan (西单) intersection, where tens of thousands of commuters, shoppers or visitors from outside Beijing pass every day. It is said that the first dazibao is posted here on November 19 by the son of a veteran communist cadre, criticizing Mao's "misguided idea" of class struggle during the Cultural Revolution.

The wall with its many posters is easily noticed by passers-by, and the free space in front, planted with trees, is wide enough to accommodate the large clusters of people who come here especially in the afternoons and on the weekends to read the texts, debate them and take notes. Some amateur artists also use this space to show their works to the public, and the new independent journals are presented and sold here.

It is not clear which author is the first to call this place "Democracy Wall" (民主墙), but this term sticks in the minds, and becomes an expression used not only in China for places where citizens post critical comments on their governments and societies. The Wall has thus contributed to global history and language.

It is a proven fact, that the Democracy Wall could exist for so many months only due to a personal intervention by China's strongman Deng Xiaoping, just as the relocation to the more isolated Yuetan Park (月坛公园) a few months later, and eventually the dismantling of this facility and the complete ban on (critical) dazibao.

On November 27, 1978 Deng is interviewed for two hours by the US Journalist Robert Novak, who also asks about his opinion on the Wall and the critical posters. Deng answers that they were "a good thing" (好事), and he has made a similar remark towards a visiting politician of the Japanese Socialist Party the day before. The quote "It is normal that the people's masses write big-character posters, this underlines the stability in our country" is carried in the "People's Daily" the next day, accompanied by commentaries supporting freedom of expression.

But only three and a half months later new rules that have been personally initiated by Deng Xiaoping are promulgated.

All public political statements had to observe the "Four Basic Principles" (四项基本原子), i.e. the "sticking to the socialist path", the "people's democratic dictatorship", the "leadership of the Communist Party of China" and "Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought". Any demands for "Western" democracy, party pluralism or unrestrained freedoms of expression and media were therefore not allowed any more. It would still take two years to fully enact this rule.

Wei Jingsheng, the editor of the journal "Exploration" (Tansuo 探索), reacts with a sharply-worded attack on Deng Xiaoping, whom he calls "a dictator ... no different from Mao".

Deng is seemingly furious: Wei gets arrested on March 29 together with a few other activists, later on police also proceeds against some civil rights defenders who demand Wei Jingsheng's release. But sanctions against democracy campaigners still remain limited to a few cases, also the Democracy Wall and most independent journals continue to exist for the time being.

On December 6, 1979, after more than a year of its existence, the Beijing Municipal Government orders the closure of the poster wall at the Xidan intersection. According to a decree by the Public Security Bureau, dazibao are from now on only allowed in a specially provided place in the Yuetan Park in western Beijing.

Authors have to show ID cards and register their posters beforehand, which is done by an approval handstamp affixed to the papers. Only a few continue to use this more or less secluded facility. At the Xidan wall municipal cleaning brigades remove all traces of posters that very night.

At a party working conference on January 16, 1980 Deng Xiaoping delivers a political death blow to critical posters and the Democracy Movement, attacking "so-called democrats" and "dissidents" whom he calls "factors of instability".

Deng asks to remove article 45 (that guarantees the "Four Big Freedoms" including big-character posters) from the constitution, which actually happens in September 1980. Shortly afterwards the nowadays sparsely used Democracy Wall at the isolated Yuetan Park is also closed down.