Interdictions, harassments, arrests and other police sanctions ...

... against individuals associated with the Democracy Movement have occurred from the beginning. After the arrest of Wei Jingsheng on March 25, 1979, the movement also turns into a campaign for the release of political prisoners as well as for freedom of expression and unimpeded political activities.

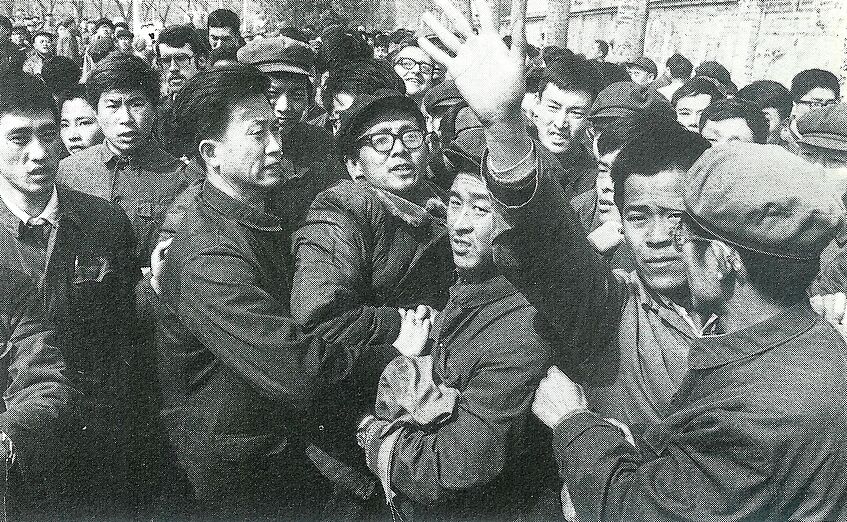

Arrest of Ren Wanding (with glasses) of the journal "Human Rights in China" by plain-clothes policemen at the Democracy Wall (April 4, 1979)

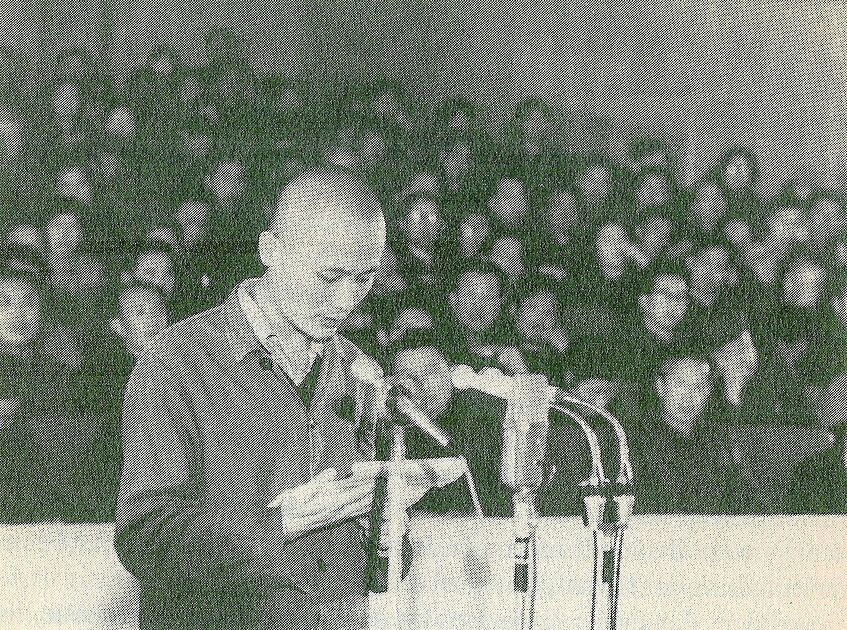

Political detainee Wei Jingsheng defends himself at his court trial in October 1979. He is accused of "counter-revolutionary" activities and "betrayal of state secrets". His defense speech is clandestinely recorded and later published by independent journals.

In 1979 Deng Xiaoping has succeded to consolidate his power at the top of the Party leadership (without formally holding the office of prime minister or general secretary of the Party). This it seems has also changed his attitude towards the Democracy Movement.

In the early days he has called the Democracy Wall a "good thing", and he emphasized to foreign correspondents that he did not fear people speaking out. But now, in internal debates such as the Theory Work Forum in early 1979, he is reported to have called activist "enemies of socialism" and a "danger" for the stability of the country.

More often than before, he now speaks of the "Four Basic Principles" for any public expression of opinion. They do not allow to question for example the leading role of the Communist Party, Marxism-Leninism and Mao Zedong Thought. State media regularly quote Deng's statements in their commentaries and analyses, usually without mentioning his name. But everybody knows now that the word of the new most powerful man in the leadership has become sacrosanct, almost like Mao's sayings in the past.

Also the constitutional changes that abolish the "Four Big Freedoms" (of expression and of writing big-character posters, among others) go directly back to comments by Deng Xiaoping.

Even top officials of the reformist faction like Hu Yaobang who has become the party's general secretary in 1980, cannot dare showing potential sympathy for the Democracy Movement any more. When Wang Ruoshui (王若水), one of the chief editors of the main party newspaper "People's Daily" (and close ally of Hu), briefly meets democracy activist Xu Wenli in 1980, he immediately becomes personally criticized by Deng Xiaoping, who questions Wang's fundamental political stance.

The Repression of April 1981

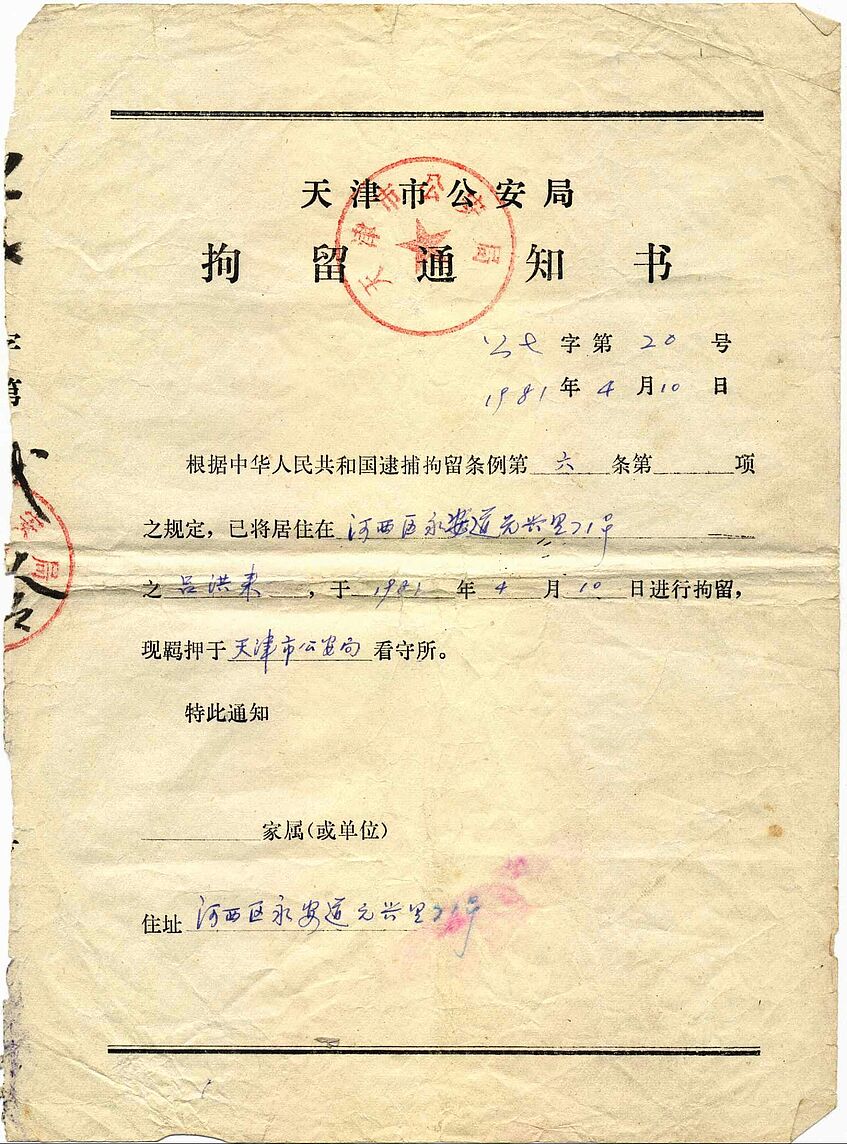

Arrest warrant against civil rights activist Lü Honglai (editor of the "Bohai Shores" magazine ) from Tianjin, dated April 10, 1981. The document does not mention a reason for the arrest.

The Repression of April 1981

Following the constitutional changes that made the "Four Basic Principles" a strict guideline for any political debate, in early 1981 the party leadership led by Deng Xiaoping prepares to deal the final blow to the Democracy Movement. On February 20, the "Directive by the Central Committee and State Council on Dealing with Illegal Publications and Illegal Organizations and Other Questions" (中共中央、国务院关于处理非法刊物非法组织和有关问题的指示), to become known also as "Document No. 9", is circulated at higher state and party levels (but not yet to a general public). Authorities, it says, are to proceed against "illegal" groups and magazines in the whole country, and "ringleaders" are to be arrested and dealt with "according to the law". (A version of this document in Chinese was available on the website of the party newspaper "People's Daily", but has since disappeared. One may still find it on other sites. A copy can be seen on baidu.com.)

Things happen accordingly. In April several dozen activists and editors of independent journals are taken into custody and interrogated, most of them have to stand court trial in the following months.

Some well-known figures are condemned to harsh prison terms, among them Xu Wenli, Wang Xizhe from Guangzhou, Sun Weibang (孙维邦) from Qingdao and Lü Honglai (吕洪来) from Tianjin. Xu, Wang and Sun and a few more activists are also accused of having committed the crime of founding a "counter-revolutionary association". They had met between July 10 and 12, 1980 in Ganjiakou District (甘家口) of Beijing to prepare the formal establishment of an opposition party.

Xu Wenli is eventually condemned to 15 years in prison and the revocation of his political rights during an additional four years, for "crimes" including also "counter-revolutionary propaganda" and "incitement".

The Democracy Movement has reached the end of the line. Activists, helpers and other people who were less prominently involved and therefore not directly targeted by the authorities, often retired into private life, or they took up opportunities to move abroad for a while. This is also what most of the artists connected to the Democracy Movement did.

No one out of the more than twenty members of the "Stars" group and of the poets connected to the "Today" magazine gets arrested, with the exception of the female painter Li Shuang (李爽) who entered an intimate relationship with the French dipomat Emmanuel Bellefroid, and is put under administrative detention ("re-education through labor") for two years.

Most of the more prominent artists and writers decide to accept invitations for study visits abroad after the beginning of the new wave of repression. Mang Ke and Wang Keping move to France, Ma Desheng and Ai Weiwei to the US, Huang Rui to Japan.

De-Maoization and after

The general political climate has changed in the early eighties, still the situation remains ambiguous. The controversy between "reformers" in the Communist Party and "guardians" of Mao's heritage are to continue for another couple of years.

The leaders around Deng Xiaoping try to channel and control the aspirations and challenges that come out of the society, they strive to advance economic reforms and to open the country for foreign investment and technology, but without compromising on the dominant role of the Communist Party. Neverthless, a limited self-criticism by the party as to the excesses of the Cultural Revolution and some aspects of Mao Zedong's role in recent history is encouraged at this point.

At the end of 1980 a special court is set up in Beijing to try several of Mao's closest allies, the so-called "Gang of Four" that included Mao's widow Jiang Qing (江青), chief ideologist Zhang Chunqiao (张春桥), the Central Committee member in charge of literature and arts, Yao Wenyuan (姚文元), and Mao's personally designated successor, Wang Hongwen (王洪文).

Briefly after the verdicts ("suspended" death and long-term prison sentences) the Party Central Committee publishes in June 1981 a comprehensive evaluation of "questions of history" and Mao Zedong's role during the last decades ("Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party since the Founding of the People's Republic of China" - 关于建国以来党的若干历史问题的决议). One of the conclusions is that Mao has commited severe mistakes in the 1950s and especially during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976). Nonetheless he should still be considered a "great revolutionary", and his teachings should basically remain valid.

In the early 1980s there seems to be no space any more for publicly debating the basic demands of the Democracy Movement, i.e. political pluralism, freedom of expression and the media and the rule of law. Deng Liqun (邓力群), the conservative head of the CCP Propaganda Department, initiates several campaigns against ideological deviations and "spiritual pollution" (精神污染) that should - so his intention - bring artistic and literary activities also back under the party line.

Still, the debates on the scope and direction of political (and economic) reforms continue. The CCP General Secretary Hu Yaobang and Prime Minister Zhao Ziyang (赵紫阳) are both counted in the reformers' camp, and they both maintain various formal and informal think tanks where young experts are allowed to develop reform concepts. They draw on communist and Western experiences, but also on the Asian models of Taiwan and South Korea (who are economically successful, and have both undergone a recent democratization process). They even take up some of the ideas of the Democracy Movement, and more so, a handful of former democracy activists (such as Wang Juntao who has participated in the Peking University elections) are invited to join one of the think tanks.

During the second half of the 1980s factional controversies escalate again. At the universities there is a new upsurge of independent debate, students organize political discussion groups or "democratic saloons", big-character posters flourish again at the campuses, and in public protests of the students you hear once again some of the demands of the Democracy Movement. Even a few officially registered media such as the Shanghai "World Economic Herald" (世界经济导报) dare new debates on freedoms and democratization.

The struggles between hardliners and reformers eventually lead to the student-led uprising on Tiananmen Square in May and June 1989, an event that draws many more participants than the first democracy movement ten years before. Many of the former activists who have already been released from prison (or never been under arrest at all) joined the new Tiananmen Movement. But after the bloody suppression of the revolt on June 4, 1989, many new arrests occurred, while some remainig dissidents tried to flee the country.

It is Deng Xiaoping who has once exercised his authority in favor of violent repression. This is the end of a reform debate that has shaped political controversies inside and outside the party during more that a decade. China's rise to become a global power is the new leitmotiv that seems to supersede all other political topics.