"Educated Youth" Sent "Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside"

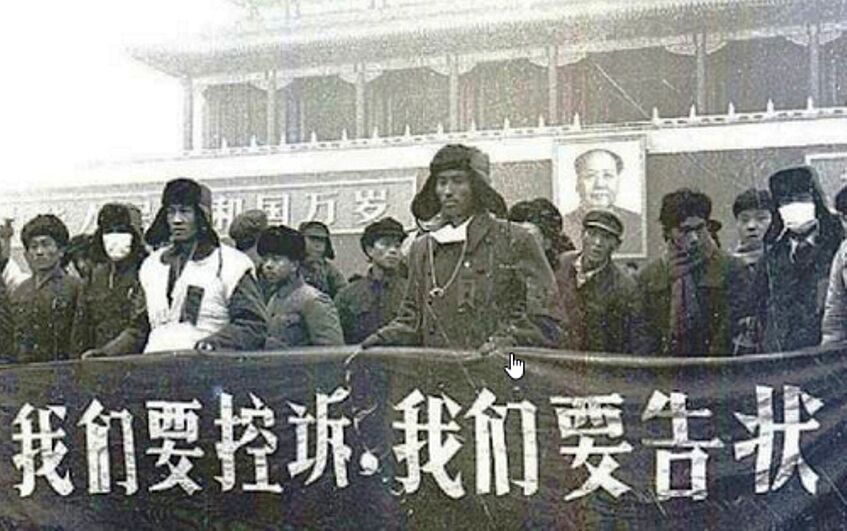

"We want to accuse, we want to sue" - a delegation of sent-down youth from Yunnan Province, in December 1978 or early 1979 at Tiananmen Square

"Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside" - the movement of sending young middle school graduates to rural areas during the 1960s

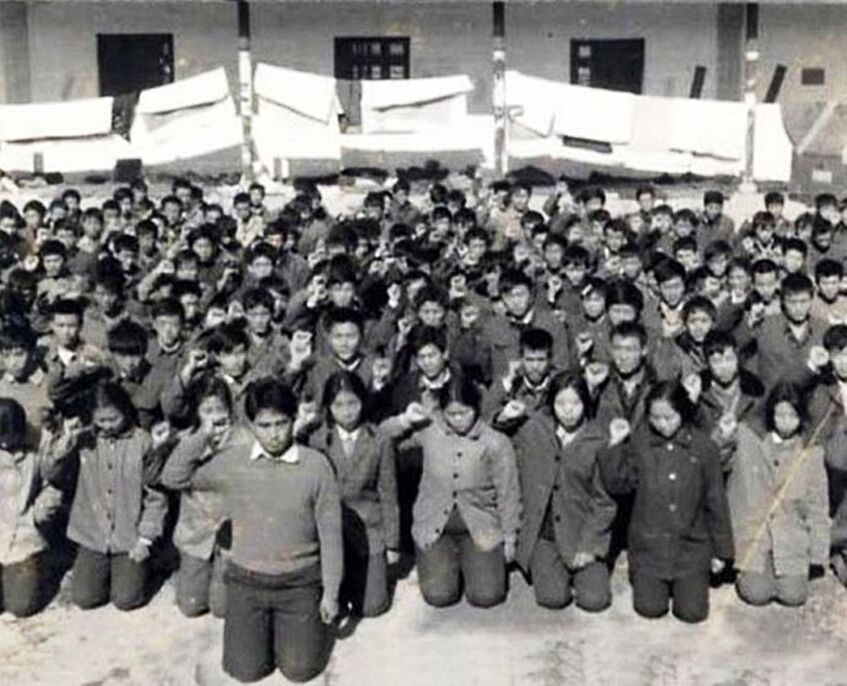

The banner on this propaganda photo says: "We will accept the reeducation by poor and lower-middle peasants and remain peasants the rest of our life".

A village welcomes "educated youth" during the Cultural Revolution.

The measure to send middle school graduates ("zhiqing" or "educated youth") from the cities to agricultural production units in poor rural areas or remote border districts (sometimes called "rustification"), has been a key Maoist policy that already had started in the late 1950s. Under the slogan "The educated youth goes up to the mountains and down to the countryside" (知识青年上山下乡), more that 17 million young boys and girls were called to settle in rural areas between 1962 and 1979. Many followed this call with great enthusiasm (fostered also by official propaganda and by the expectations of great adventures by the young people who were just between 15 and 18 years old), others gave in to social pressure, and most of them left against the will of their parents.

Roughly three quarters of the youths went to areas not too far from their hometowns (e.g. young people from Shanghai were often sent to village production brigades in the neighboring provinces of Anhui and Jiangsu), but 2,9 million still ended up in distant and little developed border regions of Xinjiang, Inner Mongolia, North-East China or Yunnan in the southwest.

These youths were usually not integrated into existing villages (often inhabited by ethnic minorities), but organized in paramilitary Production and Construction Corps (生产建设兵团) that cultivated vast state farms (such as the rubber plantations in southern Yunnan) or reclaimed sparsely populated desert and steppe areas for agricultural use.

But there was also a strategic and security logic behind the re-settlement of millions of young people from China proper: The (Han) Chinese element should be strengthened in order to control the minorities and to guarantee a better border defense in case of a conflict with the "external enemy" (usually meaning the Soviet Union).

Many youths who had come full with zest and enthusiasm to the countryside, soon found out that living conditions there were far below their expectations (and the promises made by the cadres). Housing, food provisions and medical care proved extremely poor compared to the cities, and in many villages the peasants did not welcome the "educated youth" who should also teach them technical skills and Mao's revolutionary theories. They just considered them additional eaters who were little used to the hard rural labor.

Growing Discontent

This photo is said to have been taken at a public execution of eight Beijing youths sent down to the Ningxia region (1968)

Protests in Xishuangbanna (Yunnan), December 1978

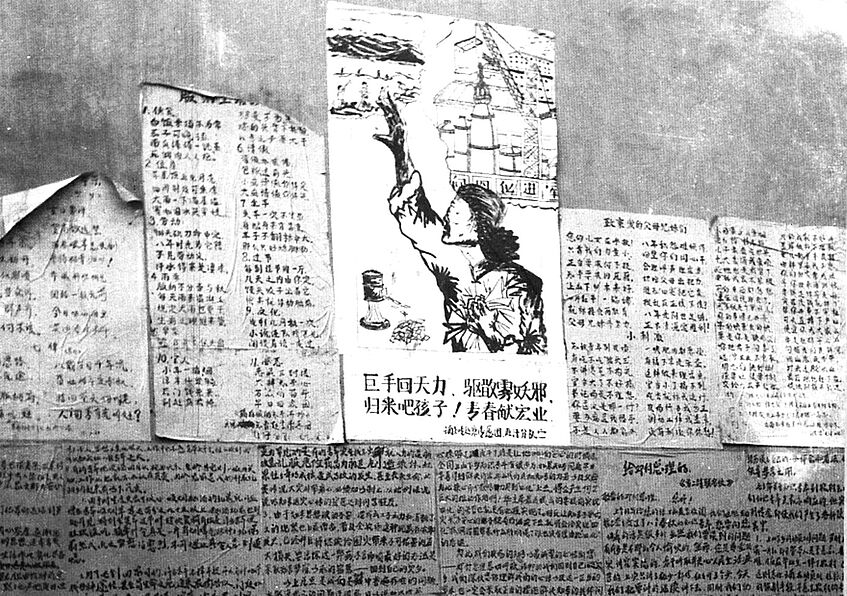

Posters put up by protesting youths in Xishuangbanna (January 1979), including the famous Open Letter to Deng Xiaoping. The text under the sketch says: "A mighty hand takes back the force of heaven, dispels the mist and chases the evil spirits. Children, come back! We want to devote our youth to the bigger cause" (= the "Four Modernizations").

Growing Discontent

In the production and construction brigades under military leadership, many youths suffered from the strict rules of discipline and the wide-spread corruption among officers who liked to split the few privileges available (such as study or work posts in a city) among themselves. Moreover, corporal punishments (including torture and beating up) were common as well as sexual harassment of girls, and harsh verdicts by the military courts including executions.

All this led to various forms of discontent. Within two years after Mao's death, the whole country experienced a mood of changes and reforms. Starting from around October 1978, this also created protests and demands for going home among the young urban people in the villages, a veritable "wind of return to the cities" (返城风) as people used to call it.

Especially the border regions of Xinjiang and Yunnan saw a wave of organized grass-root protests. There were large meetings of "educated youth" that elected independent representatives and chose delegates to travel to Beijing and other cities. There were also strikes and attacks on government offices, Beijing and Shanghai saw street rallies by some youth who had returned on their own, and they posted their resolutions at the local democracy walls. This homecoming movement with its forms of protest and self-organization also fueled the still budding "Beijing Spring".

The Central Government and the provincial leaders eventually gave in to the demands of the young people. It is said that Deng Xiaoping also ordered the authorities to find solutions instead of suppressing the movement. In the course of the year 1979, three quarters of the youths all over China, were able to return. Only in Xinjiang the return movement was suppressed at first, and the conflicts broke out later, at the end of 1979 or even during 1980.

The destinies of the "educated youth" sent down to the countryside, continued to stir up emotions in the Chinese society for many years. During the 1980s and 1990s, many documentaries, TV plays, novels and academic articles continued to take up and analyze this period, and more recently the Chinese internet also provides personal memories and photos from these events.

The Returning Home Movement among Young People from the Cities in Yunnan Province

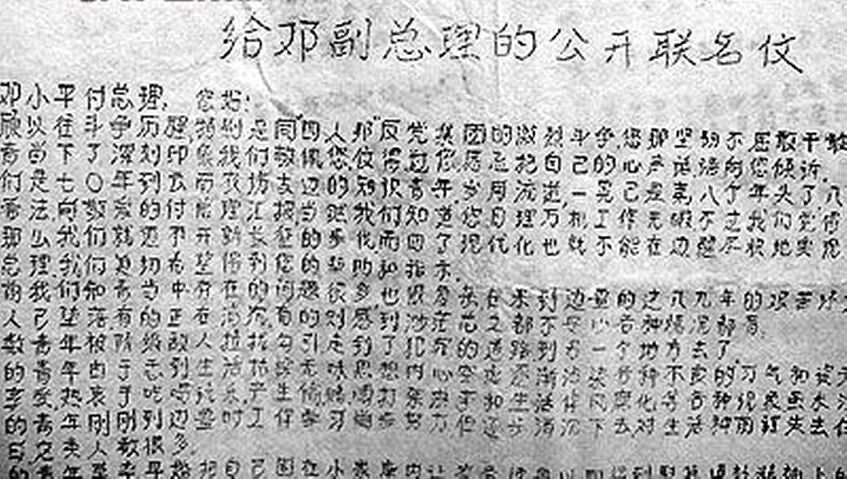

Flyer with the Open Letter to Deng Xiaoping (October 1978, initiated by Ding Huimin, the leader of the movement)

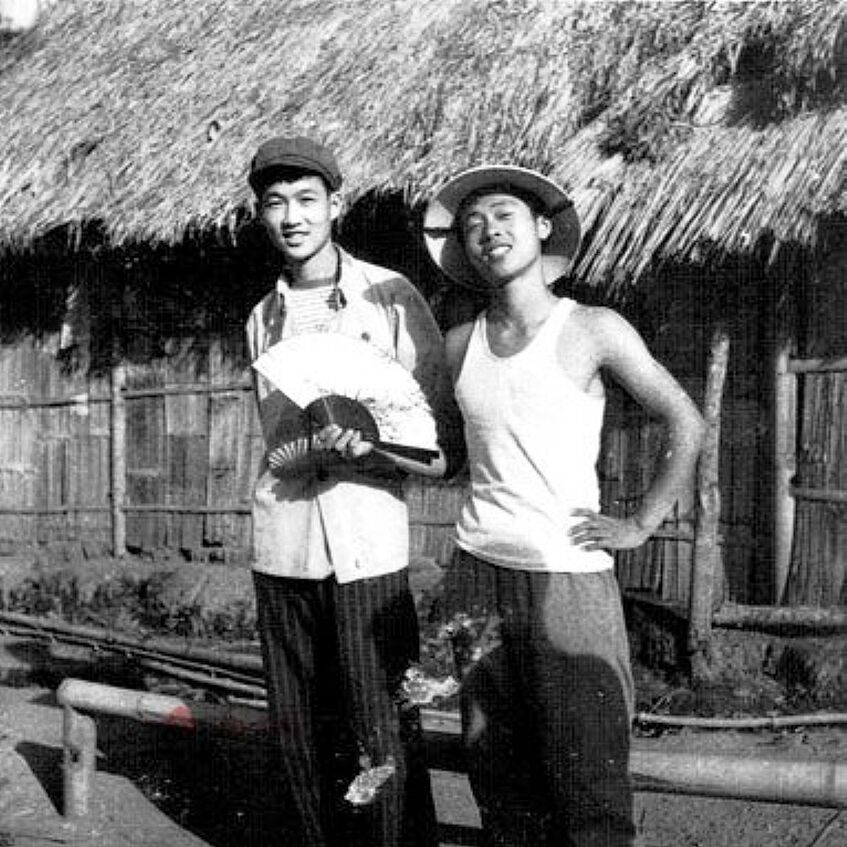

Ding Huimin (left) with a colleague, in front of a typical bamboo house in Xishuangbanna

Street march in Jinghong (Xishuangbanna) on December 9, 1978. Banners demand meetings with CCP Chairman Hua Guofeng and his deputy Deng Xiaoping.

"We Want to Return to Our Home Places" (Jinghong, December 9, 1978)

The Returning Home Movement among Young People from the Cities in Yunnan Province

At the peak of the Down to the Countryside Movement, there were some 100.000 urban youths in Yunnan, a relatively small number compared to the rest of China. But it was this province that saw the most vigorous protests at the end of 1978 and in early 1979. It was there where the first open conflicts between sent-down youth and authorities took place, and where the national returning home movement began.

Details of this political dispute have meanwhile been well documented in and outside China (see for example Bin Yang: "We want to go home!" The Great Petition of the Zhiqing, Xishuangbanna, Yunnan, 1978-1979. In: China Quarterly no. 198, Cambridge University Press, June 2009, pp. 401-421, citing many sources and articles).

As early as July 1973, official Chinese media had reported on the allegations raised against those responsible for the sent-down youth, after Prime Minister Zhou Enlai had personally received many complaints and reacted, speaking internally of "fascist activities". Already during the mid-70s, some people managed to return to the cities, but in autumn 1978, new protests flared up. Ding Huimin (丁惠民), a youngster from Shanghai, becomes the leader of the movement in Yunnan's Xishuangbanna Autonomous District (西双版纳自治州). He writes numerous letters of protest to the leaders in Kunming and Beijing, including in October 1978 an open letter to Deng Xiaoping signed by hundreds of young people, and a manifesto he calls "The Voice of Our Hearts". They demand a dialogue with the central leadership, but also threatens with action.

On November 23, the "Chinese Youth Daily" (中国青年报) takes up the issue, demanding "solutions" for the grievances of the sent-down youth. The general atmosphere of change, and the factional fights inside the Communist Party make the young people even more daring. At the end of November, more than 50.000 of the Yunnan youths participate in unauthorized meetings to elect their own leaders and delegates and to pass resolutions to the authorities. Although the government cadres realize what is going on, they still keep quiet, hoping for swift decisions by the Central Government.

On December 8, 129 elected youth delegates meet in Jinghong (景洪, government seat of Xishuangbanna) to draft new resolutions and petitions and organize a delegation to negotiate. On the following day, sent-down youth march through the streets of Jinghong and call for a strike. Groups are selected to travel to Shanghai, Beijing and Chongqing to talk to politicians and enlist support for the return home movement. Nobody is talking any more of just "improving the situation", returning to the home cities has become the only demand by now.

A Sent-Down Youth Delegation from Yunnan in Peking

Rail blockade at the Kunming Station (a scene from a Chinese TV play after 2000)

The petitioners' delegation from Xishuangbanna, led by Ding Huimin, presents itself at Beijing's Tiananmen (late December 1978 or early 1979)

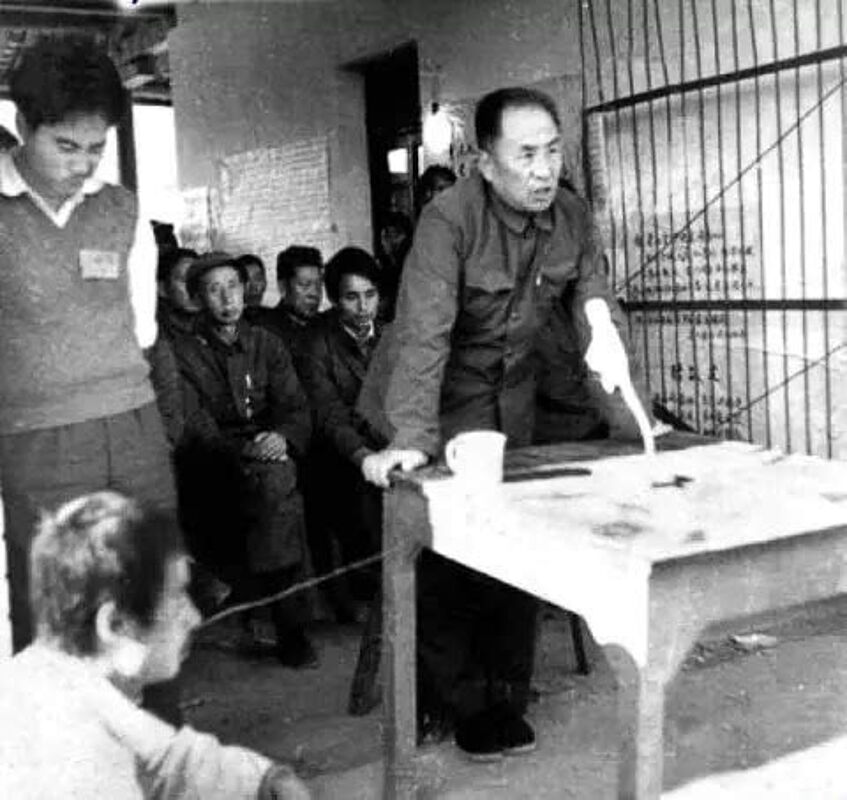

Public meeting of the fact-finding mission sent by the Central Government in Jinghong (Xishuangbanna), January 1979

Hundreds of sent-down youth kneel in front of the officials from Beijing to emphasize their grievances and demands.

Zhao Fan of the "Central Bureau for Land Reclamation" eventually announces a general permission to return to the original hometowns.

A Sent-Down Youth Delegation from Yunnan in Peking

Talks with a provincial "Work Group" sent to Jinghong end without results. The young people are even told that they were expected to spend their whole lives in the state farms and villages. The groups selected to forward petitions, set out for Beijing and other cities, but the local authorities in Kunming try to prevent them from leaving. Only after a three-day rail blockade at Kunming Station and threats of new strikes, they are allowed to depart.

The group led by Ding Huimin arrives in Beijing on December 27. They parade through the streets of the capital , showing banners that demand meetings with party leaders Deng Xiaoping and Hua Guofeng. Later they hold speeches at Tiananmen Square and distribute leaflets.

Deng and Hua are not willing to receive the youths from Yunnan, but eventually Vice Premier and Politburo member Wang Zhen (王震) sees them and promises to forward their demands to the highest level. The Central Bureau for Land Reclamation (农垦总局) is finally asked to send a high-ranking mission to Xishuangbanna, led by its directors Zhao Fan (赵凡) and Liu Jimin (刘济民) who are charged to find a solution for the demands of the "educated youth". Ding Huimin and the others also return to Yunnan.

When the government delegation arrives in Xishuangbanna, more that 30.000 young people are on strike, and the directors from Beijing personally take note of the grievances and ills that have caused the anger of the young people. At a public meeting in Jinghong held by the delegation from the capital, hundreds of sent-down youths kneel down in front of the officials - in a ritual once performed in front of emperors - to lend weight to their pleas and petitions.

Still in January, the decision to allow a general return to the cities is announced to the young people. The new urban residence permits (hukou 户口) are swiftly issued, and when it becomes difficult for the local authorities to handle the crowds, they just leave the official seals in front of the doors and fences so that everyone could use them to endorse the prepared residence and travel permits. In the course of this general obsession to return to the cities as quickly as possible, tragedies happen in some families: Urban people who have got married to local,s convinced that they would never be able to leave, now ask for a quick divorce, and in some cases even children are abandoned. By the end of 1979, 94 percent of the urban youths in Yunnan have returned to their original home towns.

The Conflict in Xinjiang

In other regions as well, sent-down youth feel encouraged now to fight for their return. In one province after the other, in Jilin, Heilongjiang, Inner Mongolia, in Shaanxi, Anhui or Guizhou, similar movements arise. But the Central Government has already decided to end the Maoist policy of sending young people from the urban centers to the countryside. Only in the Muslim-dominated Xinjiang Autonomous Region problems remain, the authorities are seemingly not prepared to release such a big workforce from the state farms and construction brigades. The conflicts here escalate later, at the end of 1979 or in 1980, at a time when all grass-root protests are already banned and suppressed in other parts of China.

In 1980, more than 4000 youths occupy government offices in towns like Aksu, Kashgar and Korla, police responds with wide-spread arrests. Only in November 1980, Xinjiang authorities also allow a general return for those young people who have been sent down to rural areas under Mao.

Many of these youngsters in Xinjiang originally came from Shanghai, some groups had already returned without authorization in 1979. They now post their personal accounts at the local democracy wall, and they begin to support the new Democracy Movement. But some forcefully storm into government offices, and they block rails to stop all long-distance trains in and out of China's biggest city, leading to some harsh police reaction also in Shanghai.