Xu Wenli

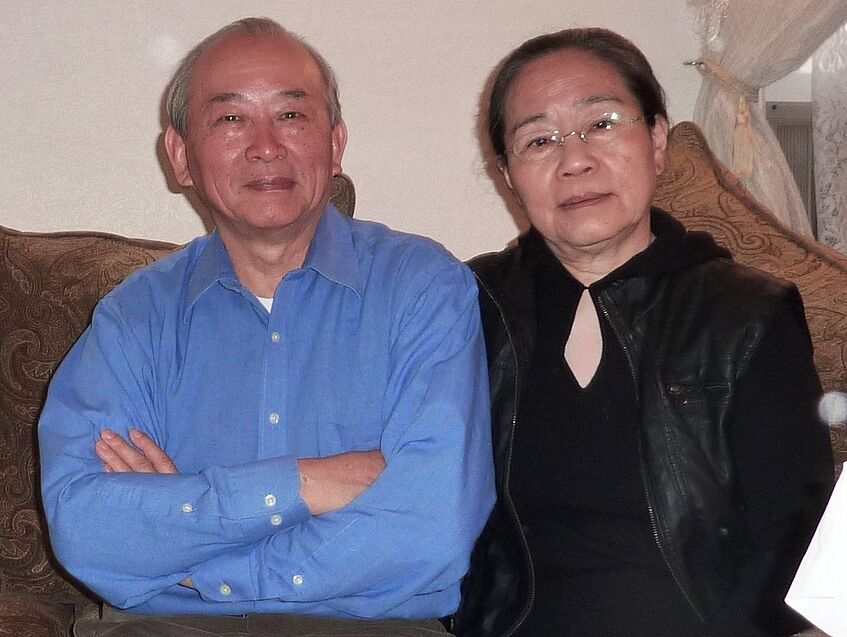

Xu Wenli and his wife He Xintong (2014 at their home)

Xu Wenli

... was born in 1943 in Jiangsu province. From 1964-69 he served in the People's Liberation Army before being assigned to a post in the Beijing railway administration. In the late 1970s Xu became a leading figure of the Democracy Wall Movement. In November 1978 he published the first issue of the journal "April 5th Forum" that continued to appear for two years. On April 9, 1981, Xu Wenli was arrested together with other leading dissidents. In June 1980 he had discussed the founding of an opposition party at an activists' Meeting in Beijing's Ganjiakou District. Because of this he was formally accused of trying to form a "counter-revolutionary organization" and sentenced to 15 years in prison.

After his release in 1993 Xu continued his political networking, in 1998 he co-founded the "Democratic Party of China". He was immediately arrested again and sentenced to another 13 years in jail. The US government and many Western politicians and NGOs pressured for Xu's release, and on December 24, 2002, he was eventually allowed to travel to the United States "for medical treatment". He received an honorary doctorate at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, where he continued to teach until 2013.

Interview with Xu Wenli (on June 1, 2014 at his home in Providence, Rhode Island, USA)

Here you find the Chinese text of the interview.Interviewer (Helmut Opletal): If you look back today on the "Beijing Spring" Democracy Movement between 1978 and 1980/81, what feelings or thoughts are crossing your mind?

Xu Wenli: I am 71 now. Things that happened more than 30, 35 years ago, look like youthful escapades to older people now. Although I myself was a bit older than the other Democracy Wall activists, roughly three to six or seven years older, I was still a young person too. If an older person thinks of what he has done in his youth, there is one question he has to put to himself: Was it right, and was it worth doing it? Why am I saying this? After 1949, the Communist Party had gained its power by opposing a non-democratic Kuomintang. But in the end, Kuomintang's question was, how much democracy do we need, while the communists asked, do we need democracy at all. The Communist Party criticized that the Kuomintang was not democratic, but ended without democracy itself. [...]

So after 1949, democracy gradually disappeared from China, we still had the Political Consultative Conference [a parliamentary body regrouping various minorities and remnants of non-communist parties], the democratic groups still had some independence, but all that ended by 1957. It was also in 1957 when Chinese intellectuals revolted last time. During several decades, Chinese intellectuals did not speak up anymore, actually nobody at all could speak openly. It was in the 1976 "April 5th Movement" [Tiananmen Square Protests commemorating Zhou Enlai] that people started to become anti-Maoist, but this was not very easy.

Only in 1978 at the Democracy Wall, this mood turned into expressing differing views and opinions through independent journals and organizations run by the people. So when I joined the Democracy Wall Movement as a young man, this movement had definitely become a milestone on the road to progress in democracy. Looking back today, I have done the right thing, and I did not just commit a youthful aberration. Maybe I did not think too much about my own safety and possible dangers. But we did have this sort of courage and did not think what we could gain or lose. From today’s point of view, the Democracy Wall Movement was necessary. It was a milestone on China's way to democracy, even though there were some aspects we did not do as well as we should have.

Interviewer: When did you first get in touch with the ideas of democracy, reform and liberalization?

Xu: For this I have to talk a bit of my family. My father was a doctor during the war against Japan, he was teaching at a medical school. He had to evacuate his students to the south, but when he saw many fighters not just dying, but nobody helping the wounded, he encouraged his students to stay with him. So the work and the background of my father were all connected to the Anti-Japanese War, and that has also greatly influenced me and my personality, mainly in two respects: As he was a doctor and a scientist, we were a very liberal and a very democratic family. Having grown up as a child in such an atmosphere, despite maybe some communist brainwashing, the effects of being surrounded by a family that highly esteemed democracy and freedom could not be easily lost. I was born with it, it stems from the family I grew up with.

So there were some people who have met me – like Tienchi Martin-Liao [an academic and human rights activist from Taiwan, living in Germany]. She said to me that I was different from the others in the Democracy Movement, that I did not have such a complicated thinking, that I was very simple and had an inherited attitude of cherishing democracy and freedom. Marie Holzman [a French sinologist] told me, that my way of speaking was different from others, and I never just say that something were for sure. I always say maybe it was like that, and I were able to respect the opinions of others.

Some academics from Taiwan I have met, have also told me that I was different from others from the mainland, more like from traditional society, the "old society" as the communists would say. Why that? Maybe because I grew up in such an environment, my thinking is not that complicated, and it was natural for me to endeavor to democracy and freedom.

Another thing was that my father had a big family. We were eight children, and I was the last one. During the war he not only took his students to the frontline, but also three of us children. And he stayed eight years during the whole war against Japan, because the country and the nation needed him to help the wounded soldiers. This spirit of my father, serving the country and the Chinese nation, has also greatly influenced me. Such a family background made me carry a high responsibility towards my country and people, and I could not be brainwashed that easily by the communists. I do not say it never happened; it certainly did sometimes, but not so much. I was also attached to politics and literature and read a lot of literary works from the West. These books were full of such ideas of freedom and democracy and human rights.

Interviewer: How did you manage to read such Western literature?

Xu: At that time one could still go to a library and borrow such books...

Interviewer: During the fifties and sixties?

Xu: During the sixties. In the fifties I was still a child, but when I entered middle school from 1957, I got in touch with Western literature, and I read all the books I could get hold of. That was still possible.

Interviewer: How was your family then, during the fifties and sixties?

Xu: My father had already died.

Interviewer: Was that before 1949?

Xu: It was in 1951. Then my family moved around all the time. I was born in Jiangxi province. Then we went to Nanjing, then to Fuzhou, then back to our family village. My mother went to Beijing together with a brother and a sister, while I went to Changchun [North-East China] with in-laws to attend school. So our family was moving a lot that time. In Changchun I attended a very good middle School attached to a normal school that owned many books that I could read, and I had the chance to read a lot of Western literary works and get in touch with some ideas from the West. After arriving in Beijing, I got more in touch with the society, and I could read even more books on various theories. I was very interested in the social issues, but my views were still strongly formed by the Communist Party. I was worried about "revisionism" and thought that we had to oppose the revisionism of the Soviet Union, and the so-called "Nine Points Criticizing the Soviet Communist Party” strongly influenced me. I also read some Marxist books and Lenin's biography plus some of his works which all influenced my thinking.

But it was the Cultural Revolution that profoundly changed my attitudes. I was in the army then and could see the chaos in society. I could also see the way how Mao Zedong was eulogized. Then the Lin Biao affair happened. At that time the "May 7th Cadre Schools" [combining agricultural work with the study of Mao's writings in order to "re-educate" cadres and intellectuals during the Cultural Revolution] had virtually become forced labor camps, and sending people "to the mountains and to the countryside" just meant ruining the students and the culture. That was when my ideas started to change.

Although my father had passed away, I still basically grew up among intellectuals and was not sent to the countryside. In 1963, after graduating from middle school, I did not want to go to a fenced-off university campus, but went myself to rural areas where I saw for the first time how backward they were. Later I became a soldier, and I experienced examples of discrimination and other dark chapters inside the Chinese army.

In 1969, I demobilized and "joined the society". I became a worker, which made me experience the very low status of Chinese workers. Although the Communist Party constantly declared that "the workers' class is leading everything", in reality it did not hold any power. That's why I got to think that this society was extremely unjust. Without a chance of having lived in countryside, having served as a soldier, having toiled as a worker, one could not understand the real situation of China's society. Moving only among intellectuals, like my sisters who were college teachers and researchers, one could not understand how China really was.

I got to understand how China really was. How could a great country with such a long history become that poor, how could the life of common people become that miserable? It was a direct result of what the Communist Party had done, and it convinced me that this had to change. But the time was not ripe yet, and the occasion had not yet arrived.

But in 1976 this chance had come. Three important leaders of the Communist Party had died, and the April 5th Movement could take place. Although I was not one of its leaders, I did participate in it. I learned what people thought and hoped for at that time. By 1978, some had already expressed political ideas and opinions at the Democracy Wall, and I thought we should pull together and create a magazine to make our own views public. I was probably the first one at the Democracy Wall who had the idea of creating a magazine.

This also made me apply to study journalism at Peking University [Beida], although some people say such major did not exist at Beida in 1977. But then it did. Journalism studies had moved from Beida to the People’s University, but it moved back in 1977, as part of the Journalism Department at Beida. My English was not good enough, so I applied for press history to study the development of publications in China.

Modern publication in China have come out of the people. The first Chinese newspaper was founded by missionaries in Macau, and this first modern paper was a private one, not from the government. During the nationalist period before 1949, many private papers existed, and I thought it should not only be to the Communist Party to decide everything, the only one that had the right to speak out. There should also be something from the people.

When I wrote my introduction to the April 5th Forum, I particularly emphasized one point: On the 9,6 million square kilometers of China's soil – with the exception of Taiwan (I did not mention Hong Kong at that time) – there was not a single private periodical, so we could start publishing one. That is why on November 26, 1978, I pasted a kind of newspaper to the Democracy Wall, calling it "April 5th News", it was the forerunner of the "April 5th Forum".

So why did my thinking change? Of course I was influenced by my family, and I had read Western literature and political works, including books by Karl Marx. I remember very clearly, that Marx, at his time, opposed the censorship of books and periodicals. And he was against keeping political prisoners in solitary confinement. He clearly stated in his writings that solitary confinement was a very cruel punishment. This was also in line with the degree and concept of democracy and freedom that I had inherited from my family. In the end Marx created a very totalitarian communism, but from Marx' books we can see, and not only from today's analysis, that at his time he criticized the lack of democracy.

Interviewer: Would it be correct to say your family did not suffer from communist repression in the fifties and sixties?

Xu: It was not very much, but there was some at the beginning of the 1960s. That was the time when class struggle and family backgrounds became important. When we had to fill in questionnaires, there were two answers they wanted: One was that my father was a doctor in "the enemy's army". In fact, my father was a general in the war against the Japanese. He fought for the nation and its people, so what does "the enemy's" mean then? But the communists insisted he was with the Kuomintang [Nationalist Party], so he was an "enemy's" army doctor. [Translator's note: His unit fought for Chiang Kai-shek at the beginning, but later joined the communist troops in their resistance against Japan.]

But there was a big contradiction, as my father was also named a "revolutionary martyr" because he had died "in public service". How come? During the Korean war, the communists suspected the Americans to drop biological bombs not only in Korea, but also on the Fujian frontline [opposite Taiwan], and they asked my father to go there, because in fact he was not really a surgery specialist, but he had studied biology, so he was ordered to do some investigations there.

My father always wanted to do his best, so the unit he tried to arrive there as quickly as possible during several days and nights. But there was a flood at the Min River, and my father’s truck dropped into the water. Most of the people died, only few survived, and the dead were the first victims "in public service" after 1949. This way my father had also become a "revolutionary martyr". So when I filled in the form on my family background, I felt obliged to write "enemy army doctor" and "martyr" at the same time. That created some problems for me, later as a soldier, I did not have any problem, that’s why I say that my family did not directly suffer from communist repression.

But when the Cultural Revolution started, we actually did. For example, my elder brother was accused of being a "son of an enemy army doctor", one sister was also attacked, but they were not locked up like others.

My father had also fallen victim to the "Three Anti" and "Five Evils" campaigns [targeting former Kuomintang collaborators]. Just after the establishment of communist power, they started to harm my father which deeply unsettled me. My father was the director of a hospital, and they just said every Kuomintang official must have been corrupt. Maybe today every communist official is corrupt, but for my father this sounded strange. We had been at the front-line to serve the nation. Because our family was big, we did not have any possessions at all, only one wooden chest per person to store our things when we moved back and forth to the front-line. Still the communists locked my father up, ordering him to confess. They kept lights on all night, preventing him from sleeping. That is how they tried to demoralize him, "cooking the eagle" as they said. But after one week they released him, I was very irritated by this. When my father came back, he talked to me...

Interviewer: That was when?

Xu: Around 1950, when the "Three Anti" and "Five Evils" campaigns had started, and intellectuals and people who had worked with the nationalist army came under pressure. In the past I did not know that my father had been a major general of the Kuomintang. Only during the Cultural Revolution, when my brother was targeted, when they said that they had found some documents in the Nanjing archives that proved that my brother was a “bastard”, a “bastard son of a Kuomintang army doctor in the rank of a major general”. Only then I got to know that my father was with the KMT during the Anti-Japanese War.

But it’s not because of my personal hatred. I still thought that China had good conditions and could do better, and it shouldn’t be a country where people starve to death. How could such troubles arise, and after ten years of turmoil, the entire country's economy was about to collapse. My personal thinking was that the Communist Party had power to restrain and stop things. They could do whatever they wanted.

Interviewer: When you considered starting a publication, did you think about it entirely on your own or together with...?

Xu: Basically, I thought about it myself, I was only one other person starting this magazine in 1978...

Interviewer: The "April 5th News"?

Xu: That one was only posted on the Democracy Wall. It was entirely handwritten and not mimeographed and circulated. Publishing started with the "April 5th Forum".

Interviewer: You said there was someone else then?

Xu: Yes, there was a person who also took the exam for the newspaper history major at Peking University. His name was Dai Xuezhong, but later on he did not actually participate in the Democracy Wall, only at the time of the "April 5th News". I took the initiative and asked him, how about we start a publication together? He agreed, and we wrote it together and posted it on the wall. After that he didn’t participate any more.

Interviewer: What happened next?

Xu: Later there was Zhao Nan, who lives in Japan now. He did not run a magazine then, but published an article about Peng Dehuai [a former defense minister sacked by Mao] on the wall. Peng Dehuai should be rehabilitated. Below, he had signed as "People's Forum" without writing his name.

It was also just a big-character poster, authored by two people, so he brought this other person to see me and ask if we could work together. At that time, many people wanted to collaborate. At the Democracy Wall I met Yang Guang, who later participated in [Wei Jingsheng’s] "Exploration" magazine. There was another person whose name I forgot. That day I didn’t return home, but stayed at that person’s house and we talked about starting a magazine together. But they later he did not join our April 5th Forum. Dai Xuezhong and I first posted the April 5th News, together with a contact address. Zhao Nan brought another person named Hou Zongzhe to talk to me about a merger of the “April 5th News” with Zhao Nan’s "People's Forum." […] I agreed and we combined the two names, “April” in the front, and "Forum" in the back, so we called it the "April 5th Forum".

At the beginning, we were four people, Dai Xuezhong and me, Zhao Nan and Hou Zongzhe, but Dai soon withdrew. Then we slowly integrated more people. Originally there was also Ren Wanding, but he did not stay and later founded his own “China Human Rights Alliance”.

Interviewer: After you started publishing the magazine, some differences soon arose within the Democracy Movement. There was Wei Jingsheng, who wrote his famous article and was arrested soon after in 1979. It seems that your Democracy Movement had taken different directions. How do you view this split and these differing opinions now?

Xu: I have a very bad opinion of Wei Jingsheng.

Interviewer: Was that also your assessment at that time?

Xu: Yes. Later, my evaluation became even worse. At that time I mainly thought that he was too radical, because he immediately pointed his finger at Deng Xiaoping. Also from my current point of view, his approach was not very appropriate. Why? After all, Deng Xiaoping wanted reforms. Only through reform and gradual accumulation could China move towards democracy. Although the Communist Party was maintaining its one-party dictatorship, it still wanted to reform at that time. He didn't even tolerate the reformers, but scolded them by calling their names. His approach caused the pro-democracy movement to collide with the powerful regime of the Communist Party. The result was that no one had a way out. If we hadn't taken this head-on collision approach...

However, from what I see today, there was nothing too reprehensible or particularly wrong in his approach, because the pro-democracy movement, or any kind of movement, always has different factions, some more moderate, others more radical. From his more radical point of view, there was nothing wrong with that approach. Moreover, he was intelligent enough and cleverly used a method that has been used by the Chinese Communist Party for a long time. Everything seemed very simple, like their slogans “Don’t be afraid of death” and “Don’t fear any suffering” or “Three Represents” [a theory of Jiang Zemin’s era defining a broader basis of the Party] and the “Four Basic Principles”. Then Wei Jingsheg tried five, the “Fifth Modernization”. In terms of language skills, he was very clever. This very smart side of him was easily remembered by people. I, Xu Wenli, talked a lot about political reforms that China should undergo, but it would have been better if I had simply talked about the Fifth Modernization. So that was his smart side. Moreover, he collided with the leaders of the CCP and was eventually arrested, which had international repercussions. He was smart and I should not blame him for this. But I still feel that he was just too extreme and that because of this, the Chinese pro-democracy movement could not fully develop and faltered too quickly.

Therefore we couldn’t do anything based on the theory of other democratic movements. We had to follow his fate, constantly appealing for him, constantly hoping that the Chinese government would release him, and constantly remaining in conflict. Later we obtained the minutes of his trial, published them, but no one has fully describes this yet. It actually had a lot to do with me. I organized it...

It didn't matter for me that we had different views and opinions. At first I didn’t know when exactly he would be tried, but I roughly knew that his trial was going to take place, so we were all very worried. It was Liu Qing who came to discuss it with me. He said: “Wei Jingsheng will be tried soon, after National Day and after the Stars Art Exhibition.” I told him that of course we should pay attention to this matter. I didn't know how he knew about the date, but I think it had something to do with the following things.

There was a person named Qu Leilei [also an artist of the “Stars” group] who worked for the Central Chinese TV, doing sound recordings. Qu Leilei was the son of Qu Bo, the author of "Tracks in the Snow Forest" [a famous civil war novel from the fifties]. Luckily, he did sound recordings for CCTV, and maybe they had received an advance notice that there would be a trial. So I think Liu Qing got the news about the upcoming court case from Qu Leilei. One day, Liu came to my home to tell me that according to his information the trial was about to take place. I told him that we had to watch out closely, and he said the good news was that we could get a recording. At that time, he didn't tell me it was Qu Leilei; he just said that he could obtain this recording. I answered that this was great, and once we got the tape, we would publish it. Such a recording of a trial of a political prisoner by the Chinese communists had never been published before. So I said fine, let’s discuss how we proceed.

Interviewer: Did all of you agree?

Xu: Liu Qing didn't tell anyone else.

Interviewer: What about your April 5th Forum?

Xu: In our journal, no one else was informed, as this was too sensitive. I also told him not to speak to anyone else about it, only when I gave a green light. But he didn't tell me who would be providing this recording. Then we agreed that on the day of the trial, I would take some people to the outside gate of the courtroom and ask to attend the hearing. In fact, I knew that someone was already recording it, and there was no need to go in to listen. It was a false pretense when we said it was very urgent that we went in and listened. So the officials thought that we were there to attend the trial, and they relaxed some of their vigilance. When we insisted they said that there were no more tickets. But where could we retreat? The trial was in Taijichang [a central location in Beijing], next to the Intermediate Court were some residential buildings that also housed a small restaurant. So we pretended to go there after we had been rebuffed. But we were waiting for this tape.

Then Lu Lin, the number two of the "Exploration" magazine and the main person under Wei Jingsheng, went to the gate to pick up Qu Leilei's tape. Qu had just finished recording, one was for the TV station, and the other was recorded for him. He came out immediately and handed it over to Lu Lin. Lu brought the tape into the small restaurant where I waited. I knew someone would come and hand me the tape, but I didn't know who it was. I didn’t know either that it had come from Qu Leilei. Lu Lin gave it to me, and I left quickly.

After that I had four copies made, two I hid myself, and one I gave to Wang Juntao. Wang Juntao later remembered this. I knew that Wang had some sort of official background, and I thought police might rather search our homes, but not his. So I trusted him and left one copy with him. Another one was the work tape to make a transcript. Then at my home, I closed the curtains and listened and transcribed it on wax stencils at the same time. I told my colleagues not to make any mistakes, not even in the nuances. If they couldn't understand it clearly, they should just write three dots. We weren’t allowed the slightest mistakes, as in the future, when they compared our manuscript with the actual recording, there shouldn’t be any fake text. If there are words that you can't identify clearly, I said, just write dot-dot-dot.

We were several people including me. One who helped us was Ma Shuji. We listened to the recordings, then transcribed them on stencils and printed them. Then we wrote the text into big-character posters and published them on the Democracy Wall. It all happened very quickly, basically decided by myself and Liu Qing, but we didn't tell Lü Pu [another editor of the group], because we didn't want an additional person to know. Had it leaked, we would have been blocked immediately. So the Party was completely unaware that we had obtained the recording and published it in a big-character poster on the Democracy Wall. Then we sold printed copies of the recordings. Before the sale, our entire editorial staff held a meeting where everyone agreed. I had arranged for Liu Qing to take a few people to sell it in front of the Democracy Wall.

Meanwhile I stayed at a restaurant called “Tianyuan Pickles” opposite the Democracy Wall, watching the situation from there. If there were no arrests on the other side at the Democracy Wall and things were going smoothly, we would send more copies over. I was alone watching, with a few people around me who were carrying more prints. At the corner of the intersection, there was the famous “Tianfu Jiang Garden”, selling soybean meat and pig feet. The group leader over there was Liang Daguang, waiting with his bicycle. If the sales went smoothly and there were not enough copies, I could ask someone to quickly send more. But if something happened, they would quickly disperse and hide the papers.

We had just made the arrangements. Some people were waiting there, when I noticed something happening on the opposite side. I saw a bunch of police officers coming to make arrests. So I quickly told them to leave the scene immediately. Liu Qing and I had made an agreement that if anything happened, I would not leave, but wait for him at a bank building next to the restaurant listen to his first-hand news. As soon as I saw that they started to take people into custody on the other side, I hid inside the bank building. Liu Qing arrived and told me, "We haven't sold it yet, but the police have started seizing people." As he led a few people in the front, a woman bumped into him, telling him to come with her before the police would take action. That moment the arrests began.

A man named Heizi [nickname of the poet Hei Dachun] and several others were taken away. But Liu Qing had escaped and ran to the bank building to meet me. We had agreed at the "April 5th Forum" that everyone should bear responsibility as individual in order not to endanger the journal, and that it should be Liu Qing to take the responsibility for everything. Liu Qing was willing to do this. In the bank building I told him that there was no other way but to step forward. He said he would go. One of those detained was Hei Dachun, all together there were probably two or three.

Interviewer: […] How did Liu explain the situation?

Xu: [...] He came over and said, Xu Wenli, they have arrested some. I asked how many, and he said two or three. I told him, there was no other way but to step forward and take the responsibility. It was your group who did it, I said, but if you are detained and sentenced, I will definitely work for your release. I will also take care of your mother. So he went to the police station and asked for the release of the others, saying that it was his responsibility. This was the most beautiful thing Liu Qing has done in his life. He had discussed all this with me, and I had made a promise to him to work for his release. Later, Wang Ruoshui, the deputy editor-in-chief of the People's Daily, was involved. I thought that through him I could obtain Liu Qing’s liberation, and he in fact did play some role. They did not really sentence Liu Qing to a prison term, but only to three years of forced labor. […] I then visited his mother every month. She was very kind to me. She later said, “Among the people of the Democracy Movement, Xu Wenli was a good one and he took care of me. My living conditions were not good at that time, and my life was very hard.” I went to see her every month and bought her some fruit. It remained like this the whole time.

But because of this affair, our colleague Wei Jingsheng never admitted that it was really difficult for me back then, and he has never called for my release. Never, no thanks at all. We have never asked for these things, nor did we hope for them, but I just say that this person is heartless and unrighteous. In fact, his problem does not lie in his political views or his radicalism. The most important thing is that the Chinese don’t trust him politically. Why do I say so? In 1993, when he was released on parole – I had been released first and he came later – he took the initiative to see me at my home and propose to cooperate with me. I had always felt that the Democracy Movement needed to have a flagship or figurehead, and since he was relatively well-known, I thought he should be able to shoulder this responsibility. I could support him, so I was willing to cooperate with him.

During this cooperation, I once made a good suggestion to him. I told him that the US Deputy Secretary of State John Shattuck was visiting Beijing, and this would be a very good opportunity for us. We should contact the US Embassy for a private meeting with him, not in public or to be publicized. The first time it would be Shattuck. The next time maybe someone from the United Nations, or leaders from other countries, and we could meet them all in private. Although private, the Communist Party would know about these meetings, so let's see if they tried to stop them or if there would be any other reaction. If not, then it could become a regular thing that our dissident leaders meet officials from the US, other Western countries or the UN whenever they visited mainland China.

Interviewer: What year was that?

Xu: This happened in 1994, when the US Deputy Secretary of State responsible for human rights affairs visited China. I had obtained this news through a Reuters correspondent in Beijing named David Schlesinger. To assist Wei Jingsheng, I told him about it and said it could become a regular practice that all important officials from the US, from Western countries and the UN meet us in private. In this way, the opposition became gradually legitimized. We shouldn’t be too presumptuous. But if we meet once, and they know it and still don’t say anything, then a second time and a third time, this would gradually become a rule. But we shouldn’t show off at first. He agreed and asked his secretary Tong Yi to contact the US Embassy. The Embassy agreed and they met. The United States also asked Wei Jingsheng that we take this matter as it was without talking too much about it in public. But Wei broke his promise. As soon as they had fixed the meeting place, he immediately contacted a correspondent to wait outside and gossiped with him about the meeting. His personal interest and the international effects were his first priorities, while the long-term political objectives came second.

To the United States, he had arrived seven or ten years earlier than me [actually in 1997, five years before Xu Wenli]. With his meeting with Bill Clinton it was the same thing. They had agreed to meet informally without any announcement in the White House library. The two of them met and it was not to be made public. Again, once he had left the White House, Wei immediately held a press conference, telling how he had met Clinton, and how he had taught Clinton a lesson to understand the evil of the Communist Party, etc. So at both occasions there was a breach of trust. Politically he is not reliable by not acting according to agreements taken in advance. So as a politician, he doesn’t have any credibility... Why did Wei Jingsheng come to the United States? Because the West and the US treated him like an important national leader of China in the future. However, after he had broken his promise in the Clinton incident, he was not trusted anymore. He should have gone to the UK to meet with the British Prime Minister, but he didn't receive him and asked his foreign minister to meet him instead. The foreign minister didn't see him either, so he started cursing the people in the UK. He accused the British of not daring to meet him because of pressure from the Chinese Communist Party. Of course I don't know all the internal reasons, but I imagine that the British thought Wei Jingsheng was not reliable and that it was dangerous to deal with people like him. I had told him before that if he went to the media to hype up his own reputation, they wouldn’t want to have contacts with a political figure like him. Leaders of important countries like Britain, France or Germany had all prepared meetings with him, but they did not materialize. No one later wanted to meet him because he didn't keep his word.

I think during the time of the Democracy Wall, he was a bit extreme and he challenged Deng Xiaoping by name. Although some people say that this messed up the Democracy Movement as a whole, this is exaggerated. He still had the freedom to provoke and write radical things. But not being reliable in politics is appalling. People would start looking down on China's Democracy Movement and not dare to deal with our activists. So from Wei Jingsheng's radicalism during the Democracy Wall to his lack of political credibility later, plus the fact that he has used money for personal aims, he all together played a negative rather than a positive role for the pro-democracy movement.

It's not that I, Xu Wenli, did not have the power to change this situation. But some people still follow him and believe in him, so it's impossible for me to change and reverse it. I also left China quite late. Except for teaching at the university, I never got a penny from the US administration or any Western government, and no one supported me, I only used my own money for my work. But he received tons of money and lied about it.

Originally, the US government was prepared to give his people two million dollars, but he said they refused to accept it because of the conditions attached by the Americans. But this was not the case. In fact, some of them were fighting fiercely for the money. From then on, Liu Qing and him didn’t talk to each other anymore, the same with Wang Dan [a leading 1989 activist] and him; and he also split from Harry Wu. They were four people at the beginning, in the end there was only him. The US government proposed to support them if they pulled together. But in the end, the four of them were fiercely fighting each other, and the US would do nothing. Who should they give the money in the end? It couldn’t be handed to just one person. But Wei’s idea was that it should be given to him.

He also told a Hong Kong branch group of the pro-democracy movement that the money they had accumulated in the name of the Democracy Movement in China should also be used for the Chinese movement. They agreed, but Wei demanded that it was given to him. These people in Hong Kong were confused and didn’t want to give it to one person alone. He said, if you don’t believe me, who else can you believe? I am the Democracy Movement and its leader. I represent the entire movement. But the Hong Kong people insisted that their financial system was different, they could not trust just one person. Things had to be discussed and approved by everyone, and there was an accounting system. How can we just give it to you?

All this, starting from the Democracy Wall, was not the biggest problem. The biggest problem was a series of subsequent performances, the breach of political trust, the lack of credibility, considering himself the natural leader of the movement, then spending money excessively and finally damaging the entire Democracy Movement. That we cannot reverse, even if we want to.

Interviewer: A completely different question: In 1978 and 1979, did you have contacts with representatives of the political system, with high-ranking Party or government officials? And how did they talk to you, could you directly meet any of them?

Xu: Personally, I did not have any direct contact. But some others told me that they had been contacted by representatives of the Communist Party, and they were even offered important positions in the Central Committee or Secretariat of the Youth League. I myself never received such propositions from a Party representative, but I did have a personal contact twice. Once I took the initiative myself to meet [Deputy Editor-in-Chief of the "People's Daily"] Wang Ruoshui, because I thought the paper could use its big influence to do something for Liu Qing [who had been arrested for publishing the secretly recorded transcript of Wei Jingsheng's court trial]. In our view, Liu Qing's doing had not been illegal as it was a "public" trial, and it should be allowed to publish the proceedings.

Interviewer: Was it your initiative to see Wang Ruoshui?

Xu: Yes, I just went to his office.

Interviewer: And he received you?

Xu: I actually did not expect to meet him in person, but I wanted to give it a try. I had never met Wang Ruoshui before. ... In reality he was an acting chief editor, above him there was only Hu Jiwei, who was more a supervising editor who did not really run the day to day business of the paper. This was Deputy Chief Editor Wang Ruoshui's job who was actually in charge of conducting the daily affairs of the People's Daily.

Interviewer: So you just rang the door-bell and asked to talk to Wang Ruoshui?

Xu: Exactly like that. I was accompanied by two colleagues, but one – as I found out later – worked for the State Security Bureau. He was certainly not a full-time agent, but probably coerced to cooperate with the security system.

Interviewer: Did he also work for the "April 5th Forum"?

Xu: Yes he did. The other person who accompanied me was Yang Jing [another editor of the April 5th Forum]. So we went to the People's Daily office to present our case and ask for support. At least we hoped that Liu Qing would be spared from a court trial. We wanted to argue that it could not have been illegal to report on a public trial. Among the authors from the Democracy Wall there were two diverging opinions. Some – including me – thought that it would be better to exert some influence on the authorities behind the scenes. I did know that the People's Daily run a publication called "Internal Reference News" intended for high-ranking officials only, and we thought it could publish certain information there to influence their decisions. My opinion was that we should not talk too much in public about this affair, but rather try to talk to people in the background. But others, including Yang Jing, held different views. They insisted to stage a protest at Tian’anmen Square and start a hunger strike in front of the People's Heroes Monument to pressure for Liu Qing's release. I thought that this could hardly benefit Liu, but would only complicate and exacerbate the case. But that is why I wanted to have someone with a different opinion like Yang Jing to accompany me. He should be able to see where his method could lead to.

But I had not calculated that Yang would ask another person to come along, that was the one who called himself Suo Zhongkui. This was probably not his real name. He was supposed to be a carpenter, and he definitely knew to make mimeograph stencils. But for sure, he had sneaked into our journal on behalf of the State Security Bureau. His first name "Zhongkui" is also the name of a deity that catches evil spirits with a chain, and it seems that this was his assignment with us, that's why he was given this pseudonym. During our meeting he always seemed to doze, not interested in anything. But he knew to make printing stencils, that’s why we hired him.

So Yang Jing had brought him along. I had not told him beforehand that I wanted to meet Wang Ruoshui, because I was not sure who was actually in charge and who we would be able to meet. I did know that they were closely monitoring the independent journals, but who was responsible for this, and how they were actually dealing with this subject, I did not know. At the reception office they made a phone call to find the person in charge or his assistant. That was Wang Yong'an, Wang Ruoshui's secretary, who then came down to meet us, saying that we were lucky as Wang Ruoshui was actually present that day. I don't remember his exact words, but he said that Wang Ruoshui was ready to meet us. So we went upstairs.

We had already prepared a letter expressing our hope that the Communist Party would correctly handle this matter and release Liu Qing. In this letter I quoted a sentence by Peng Zhen [a former mayor of Beijing] who was Acting Secretary of the Politico-Juridicial Committee. In a statement he had called for a correct dealing with movements coming out of the people, talking also about criticism and dissenting opinions from the grassroots among other things. This I had quoted in our letter. As it was my first meeting with Wang Ruoshui, I did not know yet that he was Deputy Chief Editor and a participant of the "Forum on Theory Work" [held in early 1979 to criticize political aberrations of the Cultural Revolution and Mao's policies]. This forum was very important because it was held at the time of the Democracy Wall. But I did not know then that Wang Ruoshui was a leading representative of this faction inside the Party.

We had not arrived yet at his office when he already greeted us in the hallway. We then handed our letter to him which he read carefully. He only made a brief remark: "I understand the meaning of Peng Zhen's sentence you are quoting, but I suggest you better leave it out." Hearing this I felt relief as he had understood even better than us what Peng had tried to express.

Interviewer: Why exactly should you not quote Peng Zhen?

Xu: Saying that, he meant that we should not take him too much up on his words, like telling him, you, Peng Zhen, have told to respect criticism from the people, and someone who expresses criticism must therefore not be punished. Wang did not say it like this, but it meant that Peng Zhen would possibly not be too pleased when we tried to insist on this quote. But the fact that Wang Ruoshui had understood why we cited Peng Zhen, but should better leave this sentence out, confirmed my feeling that he wanted to help us. And that we should not insinuate something to a politician as this could rather make things worse. Peng Zhen's main assignment at that time was to deal with cases of people who had been accused of being enemies of the revolution, with dissidents. So we should better avoid putting him at odds with us, and simply ask for not trying Liu Qing in court and releasing him. We then rewrote the letter and sent it again.

This was my first meeting with a high-ranking communist official, and I had met him on my own initiative. Another one was Tang Xin. He had been commissioned by the Communist Party to meet and interview us as a journalist. He worked for the "Internal Reference News" of the Beijing Daily, and he was assigned to make these investigations by three politicians, namely Deng Yingchao [member of the Politburo and Zhou Enlai's widow], Chen Yun [Deputy Chairman of the CCP] and Peng Zhen.

Interviewer: How did you know this?

Xu: This he told me much later when he had fallen himself into disgrace and was moved from the "Internal Reference News" to an agricultural department. That was because Tang Xin was the son of [former Minister of Metallurgy and Petroleum Engineering] Tang Ke.

Tang Xin had been charged by these politicians to investigate around the Democracy Wall, and he eventually drafted a quite sympathetic report on the editorial board of our journals. I was later allowed to read it, but I did not obtain a copy myself. He gave many details on the Democracy Movement and wrote up his own assessments.

Interviewer: So what was the contents of this report?

Xu: He also described the editorial members of each of the journals, at least the main ones, the number of contributors and the political views of the dominant figures. I remember well what he wrote on Chen Ziming and Wang Juntao, he described them, as well as our “April 5th Forum”, as “long-distance runners”, but [Wei Jingsheng's] "Explorations" as “short-distance runner”, adding that in politics only long-distance runners could succeed, the others would quickly falter. I remember this sentence very clearly. He also wrote on my person saying that among all the leading representatives of independent journals, I were relatively moderate and mature. It seems that among his assessments, he held the most favorable for me, and in his final remarks this sounded even more positive.

Interviewer: How did you manage to read this report?

Xu: That was later, at the end of 1979, when representatives of the Youth League Central Committee talked to us. Among them was Tang Ruoxin, who was in charge of the Policies Strategy Office, another one was Zhong Peizhang who worked for the same office. He had been labeled a "rightist" in the past. In late 1979, or maybe early 1980, it happened once or twice that they invited those of us from the Democracy Wall Movement who had not been arrested yet, for a round table to ask us about our views and opinions. It was then that Tang Ruoxin let me read Tang Xin's report, adding that they already had some good understanding of us as Tang Xin had written quite positively on our people.

Interviewer: How many were you at these meetings?

Xu: More than ten all together, a few from each of the different journals. We talked for several hours. ...

Interviewer: So mainly they listen to you and didn’t tell much themselves?

Xu: They did not say much themselves, they just asked us how we viewed the Democracy Wall, our opinions and criticisms, that's what they wanted to hear from us. I had the impression that they were rather open-minded and relaxed. When Tang Ruoxin handed Tang Xin's reported to me, he especially pointed to his conclusion on which course China should take in the future. One could actually feel that Tang Xin held sympathies for us, at least a little bit of sympathy. He concluded that there should be space for diverging opinions in China, including critical ones. It was a very extensive report. I think you should be able to find it somewhere, it was not top secret. Only later I realized that Tang Xin was also commissioned by these politicians to investigate into our personal lives, including our families. He even came to my home to interview me.

[Back to the spy in our editorial board:] At that time I was still a bit suspicious. Why could this simple conversation with Wang Ruoshui become such a problem for him? I was intrigued by this and thought that Wang Yong'an was behind it. Wang Ruoshui later excluded this possibility; he said it were our own people, one of those I had brought along. And as it could not have been Yang Jing, Suo Zhongkui was the only one who remained. We had not even resent the redrafted letter yet, we only brought it two or three days later, when the CCP Central Committee and Deng Xiaoping had already received an angry report by the Public Security Bureau, stating that Wang Ruoshui had sympathized with Xu Wenli and the independent journals.

Interviewer: How had you found out about this report?

Xu: Wang Ruoshui has told me later [when in exile in the US]. He said that as soon as we finished talking about this matter, maybe half a day later, a report from the Ministry of Public Security was sent to Deng Xiaoping's office. Deng Xiaoping was furious, saying how could our mouthpieces and people from our party's organs and publications have contact with them and offer advice in order to prevent Peng Zhen from feeling uncomfortable. The report actually contained details like this. They eventually sent Hu Yaobang to ask Wang Ruoshui why he maintained such contacts. Wang Ruoshui remained very calm, answering that there were no contacts, and it had been a random meeting. But later this meeting with us was cited as one of the reasons why he was expelled from the Communist Party and had to undergo disciplinary procedures. That happened later in the 1987 during the campaign against "bourgeois liberalization". [After being expelled from the Party, Wang emigrated to the US.] Wang Ruoshui tried to argue against these accusations. He said that he did not know who exactly Xu Wenli was. But he must have had some information on me through Wang Yong'an, and we also sent copies of each edition of the journal to the People's Daily, so they were able to read them in their editorial office. He told Hu Yaobang that Xu Wenli was relatively moderate, not like he had thought before. Hu Yaobang is quoted to have said only one sentence: Xu Wenli was somebody who only gives up when there is really no other choice. He is hell-bent to get his own way, so there is no need that you speak on his behalf. Wang later quoted this sentence by Hu Yaobang and his assessment of my person in the preface he has written for one of my books [...] So I communicated with the Communist Party at three occasions, but none of these meant that they were directly contacting me to discuss. One was their investigation, one was when I tried to solve Liu Qing's problem, and the other was their symposium.

Interviewer: How would you evaluate Hu Yaobang's attitude today?

Xu: I think Hu Yaobang was a relatively enlightened person. He even believed that our group of people could be allowed to exist as long as we accepted the leadership of the Communist Party. But he didn't realize two things, one that the Communist Party would not allow this, and the other was that he did not understand that we also could never accept the leadership of the Communist Party. So in this sense, Hu Yaobang was a bit naïve when he considered that the Communist Party should accept these people under its leadership, but he did not consider that the leadership of the Party would not be able to accept these people. He did not think that I at least – not talking about others here – that I could not accept the leadership of the Communist Party. Had I accepted it, I would not have done all these things. […] But Hu Yaobang believed that under the leadership of the Communist Party, it was possible to accept some different views and opinions, even our private journals. This was the more naive side of Hu Yaobang. He had a good heart and he was kind, but politically he was quite naive. He was different from those hard-liners in the Communist Party. Anyway, his idea was not acceptable to both sides. It was impossible for the Party hard-liners to accept such a situation: not being led by them, or even being led by them, but with strong opposition; in addition, from the perspective of the opposition, it could not accept the leadership of the Communist Party.

Interviewer: How would you evaluate the current pro-democracy movement in the United States or in the West?

Xu: Generally speaking, it’s not normal for China’s pro-democracy movement in exile to be in such a mess. I would agree with Wang Xizhe who spoke of the "Eight Immortals crossing the sea, each showing its abilities." It need not be one organization or one single leader, they could all do their own thing and play their own role. And I think everyone still plays his role, be it positive or negative, but they do have an effect. Those who actively care about the pro-democracy movement are influenced by the people of 1979 and 1989. These people bravely broke through a barrier and became successful. We cannot say that these people are a mess or that they are completely divided and have no effect at all. There is still some. After all, they are not a temporary or sudden appearance, they have long-term reflections about China's affairs, and their attitude is relatively firm. Most of these people – no matter how well they are doing at this moment – they are still carrying on. It’s not easy to persist after more than thirty years. After thirty-five years these people are still here, still talking about these issues, and still being active. It should be said that this is not all that simple, and they should be given adequate evaluation. But it is not good enough, it is not as successful as it should be, but its impact on Chinese society should be huge. No one can deny this. Talking about them, although many people don't know it, but some regard them as their predecessors and pioneers who once bravely walked into prison. Compared with them today, it’s nothing. We were sentenced to fifteen years at that time, and later even Liu Xiaobo was sentenced to eleven years. So what happened to these people in the past, is still there and it cannot be denied. They are still carrying on and basically have not given up. Although they have taken different paths and their views are very different and they are not united and quarreling with each other, but overall they are still playing a very important role.

Interviewer: There are not only different opinions in the movement, but also some serious disputes. Do you think it is inevitable or...?

Xu: I think it is inevitable because everyone has his individual perspective. One thinks something is very wrong; some others make no fuss and think it’s right. Therefore disputes are inevitable. But we should acknowledge that in 1978 and 1979, these people broke a hole into China's one-party dictatorship. And they have persisted afterwards and did not give up, which was not easy. They have encountered too many things in these thirty-five years. They could have made different careers long ago. Many of these people were in prison for more than ten years. The price paid by being in prison was huge, and it has destroyed their youth. It also destroyed their families, and their entire life took a very different course from that of ordinary people.

So the damage these people suffered was huge. I once said this at the US State Department: Don’t look down on these people. These people have fled to the United States and have no jobs, no families, no houses, and no cars. It is very difficult for them to survive in this environment, unlike you. You are Americans, you have jobs and naturally own a house and a car, and even things left to you by your ancestors. But they have nothing. They had to rely on their bare hands when they arrived here. Therefore fighting has not been easy for these people. Despite many problems and mistakes, they are still here today and persist, and they should be admired. It was not easy for them, and we should acknowledge this.

Moreover, after they had broken through this barrier, the gap for dissident forces in China has become wider and wider. During the Democracy Wall era, we only had a dozen or at most a few hundred people. But today, since 1989, tens of millions of people have taken to the streets. Of course the number shrank again later. But there are 500 to 600 million internet users in China today, and at least one-fifth of them disagree with the Communist Party and often say things that the Communist Party does not like. This number is huge, and it affects the entire Chinese society.

As the gap between the rich and the poor in Chinese society is so big now, and social contradictions are so strong, these activists in exile are certainly having an impact. At least many of them will consider them as their predecessors and use their achievements to convince some more people. People started talking about democracy so early, hoping that China would become a free and democratic country, and they paid with more than ten years, even decades of their youth for this. So to a certain extent, they have the power of role models still playing a considerable role in society as a whole. So these people should not be belittled. But overall, it is not easy for these people to survive today. Some do not have good jobs in the US, so it is difficult for them to have a stable family and life. Some have to rely on casual employment, but they are still publishing and speaking up to this day. It’s not easy.

Interviewer: The overseas Democracy Movement has received funding from various sources. Where does the money mainly come from? And how did it affect the Movement abroad?

Xu: I have never received a penny from the US government or other Western governments, so I don’t know where precisely this money comes from. But I know a bit in general. In the United States, the FDD (Foundation for Defense of Democracies) was in part created to give financial support to the Chinese Democracy Movement overseas. But now, the Foundation not only cares about China, but provides money to democratic movements around the world. Their method for giving assistance is basically a project responsibility system, money is approved for précised projects applied for.

I have never been once, nor have I received any money. In the end, I didn’t try hard enough, so I didn’t get any funding from them.

As for how some people received such funding and where their money was spent, I actually think there is a big question mark. No matter whether it has been the "Democratic League" or the "Democratic Front" in the past, or later the “Wei Jingsheng Foundation”, I really don't know how they got the funds.

But I know that there has been money provided by Taiwan, especially during the Chen Shui-bian era. Some of them don't admit it. However, when Chen Shui-bian was brought to court, he had to admit it. So I don’t know how the money was spent, but what I do know is that Wang Juntao has established a strategic research institute in Washington. Later, even the United States found out that there were problems, so it was disbanded and the money was cut. But I don't know the specifics very well.

Other people say that the organization "Human Rights in China" received millions of dollars a year, but it did not assist China's democratic movement or people suffering in the country. This is a bit exaggerated. They don’t quite understand such non-profit organizations in the West. It is important for such an organization to pay for expenses and its staff. What Liu Qing [then Chairman of “Human Rights in China”] could really control was only 100,000 dollars. Although he was the chairman, he did not control millions, only 100,000 dollars were at his direct disposal to help suffering people in China.

But he said something like Xu Wenli's people should not help him. Although he used to be my assistant and I went to rescue him at that time, he had excellent relations with Wei Jingsheng then. When he believed that Wei Jingsheng would be the future president of China and a winner of the Nobel Peace Prize, Xu Wenli criticized him. I originally didn't want to openly criticize Wei. I had a working relationship with him and knew him relatively well, so I didn't want to criticize him in public, especially since he was in prison. But Ren Wanding made it public. He had asked me about Wei Jingsheng's situation and publically quoted what I said. So I am very unhappy with Ren Wanding.

When Wei Jingsheng came to the United States, I felt that many of his practices were wrong, and I had criticized him privately. I I did not want to be a person who criticizes others behind their backs. I wanted to make my opinions public, so I criticized him openly. But his people thought that I was pro-CCP and that’s why I attacked Wei Jingsheng. They believed that Wei was a genuine leader and Nobel Peace Prize candidate, and Xu Wenli a spy of the CCP. Xu has been in prison for more than ten years, some said that this was deliberate torture scheme done to show to others, and that in fact he was a Communist spy. Around the Democracy Movement, Wei Jingsheng and Liu Qing have long spread the suspicion that Xu Wenli was a high-level spy trained by the Chinese Communists, and that he was here to undermine the movement by criticizing Wei Jingsheng. So at that time, the two of them had a very good relationship. Later, the two of them also publicly fell out over money.

In short, these are the main financial sources. One is the American Foundation for Defense of Democracies; another one relatively wealthy organizations like “Human Rights in China”; and the third is Taiwan. From the Taiwan side part of it comes from their intelligence agencies, another part from the Taiwan Independence people. Chen Shui-bian gave money when he was president. These are the sources I know of. But whether or how these can influence the pro-democratic movements, I am not sure... because I haven’t received any.

Interviewer: And from Taiwan?

Xu: Taiwan has influenced several people. For example, Wei Jingsheng wanted to get money from [former KMT president] Lee Teng-hui. So when Wei arrived in Taiwan, he said, why don’t we give independence to Taiwan? Even Shandong or any other province can be independent. He remarked that he had said this to please Lee Teng-hui. But Lee did not give them the two million, as they had just said what they liked to hear to get the money. This is a true story.

Interviewer: How do mainland institutions try to damage or influence the pro-democracy movement?

Xu: It’s what has just been mentioned. In fact, mainland China also spends a lot of money.

Interviewer: What do they spend their money on?

Xu: To sow discord. Before I came abroad, once two organizations should have merged, but the final result was that they split into three groups. Kuomintang agents and Communist agents were both at work there.

In addition, the most disturbing thing now is that if you set up any organization, like we set up the China Democratic Party, some of them use money to set up a competing organization that will be stronger than yours. For example, when we created the China Democratic Party and established a joint headquarters overseas, some people founded a “China Democratic Party National Committee”. A “National Committee” normally is the central body of a political organization. Seventeen people stayed at my house for the meeting. Because I have no money, I provided my own salary and my house to support this. About fifty more people stayed with other friends. For the meeting we had no money. But when their people hold a meeting, it will be in a five-star hotel in New York!

We all know that we as exiles don’t have much money. How can they have so much money then to rent dozens of rooms in a five-star hotel? It is said that someone provided it. I've heard this, but I don’t have definite evidences. How could they do this? It is said that they set up an external website, and then the Communist Party spent a lot of money to acquire this website. This way it was a simple business trade. My website is worth five million, you buy it for ten million. Thus the ten million came from a business relationship, not from the Communist Party, it was money earned in the United States, and they can just put it in their pocket and use part of it to hold their meetings. Do you understand what this method means? The Communist Party didn’t give money directly; they bought your website, and now you are rich fund them with your own money. That’s how complicated things my get. But I have no definite evidence on all this. I just heard that it happened like this.

They came to my place before this meeting and asked to disband our joint headquarters and merge with them. I did not agree. Not only did I disagree, but our entire headquarters disagreed. To put it bluntly, it was an initiative by Wang Juntao. Wang has nothing to do with the Democratic Party. When I first met him in 2003, he did not say, "Xu Wenli, I am very happy that you have come to the United States." No, the first thing he told me was, Xu Wenli, you must never talk to me about the Democratic Party. The Democratic Party is simply a joke. This is what Wang Juntao said. When they came in 2009 and asked us to disband, he was with them. He said he had no interest in the Democratic Party and wanted to stop it long ago. He just accompanied them. But six months later, he established the “China Democratic Party National Committee” with them.

As you see, there are also funds from the Communist Party in addition to funds from Western countries and Taiwan. They are becoming more and more influential in this regard, especially as the country becomes richer. They adopt an alternative approach. Whatever we do, they will do the same in a more ruthless way, with more money behind, so that you will not be able to compete.

Interviewer: How do you feel espionage activities by the mainland?

Xu: I don’t think they are like some say that they assassinate or poison people. This is a bit exaggerated. I personally have never been threatened this way. But what I feel is that they try to send people to approach you, several young people for example, hoping that you will assist them. One who really tricked me was a certain Yuan Bin. He said he came from the Chinese Democratic Party. I actually remembered such a person. He told me he was being persecuted. Later, I saw his injuries and had the impression that he had been persecuted, so I supported him. He didn't even have a passport. We mobilized our highest political contacts to get him from mainland China to the United States, passing through Thailand. He came to stay with me. On the first night when I was doing something on the computer, he sat next to me. My drawer was open, and from the corner of my eye I saw that he was picking at my papers. Then suddenly there was a letter from him and he was very nervous. What was going on? At the back of this letter, there was a letter I had written, but in the letter in the front the CCP was threatening him. So I knew that these people tried to come, he was a party member who had been prepared, a young man, he had been tortured. [???] So I sympathized with him and wanted to help him. When you help him, he will stay at your side. This happened, but not very often, it’s just the most obvious example.

It’s important that they can instigate very extreme things inside your organization. As a result people in China will be persecuted. People on certain lists will be exposed and then persecuted. So I think they are trying to do three things: One, they place people around you, secondly, they join your organization and often suggest some very extreme acts, and the third most dangerous thing is substitution, substitution strategy, which means that if you do something, they’ll do the same, and they will actually control it.

Interviewer: Do they monitor your email and phone calls?

Xu: I think so. Basically there is no way to keep things secret.

Interviewer: Why do you think so? Do you have any evidence or did you discover it yourself?

Xu: They have entered some mailboxes, so that people didn’t have access any more. It couldn't be done without hacking. I'm at a university, so our mailboxes are relatively free of such problems. But I have never believed that emails or phone calls can be kept confidential. I don’t want anything too secret either. If there is something really too sensitive, I will discuss it face to face. I follow this practice overseas just as I did it in China. Any sensitive matters are discussed in person. Besides, we don’t have any secrets.

But during phone calls, I sometimes have the impression of hearing an echo. At critical points, it clearly seems that that someone is inquiring about you and your plans at the other end of the line. But it is difficult to tell who it is, whether it is their people all the time. For example, during the June 4th Movement [of 1989], people who rarely called in the past would call. Where are you? I heard that you were in San Francisco or Los Angeles. Will you go to San Francisco? They tried to sound me out where I was going.

Interviewer: One thing I’d like to ask you: When you were at the “April 5th Forum”, was your intention to reform the socialist system, not to completely replace it? How did you see the issue of “socialism” at that time?

Xu: After 1949, the Marxist education we have received since childhood has made socialist ideas deeply ingrained, or we might say communist ideas. The deepest impression on us was that so-called communism meant that there would be no exploitation, no oppression, and everyone was equal. This was the theoretical indoctrination given to us. I have been brought up with this since I was a child, so I believed it and never thought it was not true. I also thought that even if it was not fully realized at that moment, it would definitely be realized in the future. So this idea was deeply ingrained. Until 1978 or 1979, I never articulated that we would overthrow the socialist system and the leadership of the Communist Party. I just felt that it was not perfect enough yet, and that there were some dishonest aspects too. Even when I visited rural areas or served as a soldier or were a worker, I saw a lot of mistakes or unfulfilled promises. But I was still convinced that things could be achieved. How? I thought the most important thing was that there was no opposition force or dissenting voice. I never thought the socialist system or the communist ideal was a problem, or that there was a need to overthrow the Communist Party to solve China’s problems.

Basically, I still reflected about the issues within the framework they had originally given to us and that in the context of the political struggle, we were very weak indeed. As you know, there were only a dozen or so people who dared to stand up during the Democracy Wall period, later a few dozens, and only a few hundred across the whole country. How could we fight against the Communist Party’s huge power? So to a certain extent, it also meant to protect ourselves, when we used catchwords of "Marxism" or "Communist leadership". As time went on, we realized that these were just phrases, something we didn’t yearn for or hope for.

But around 1979, my thinking had not reached that level yet. I still wanted to pursue a more ideal communism, where there would be no exploitation, no oppression, equality for everyone, and great material abundance. Later it became increasingly clear to me that this was fake and impossible to achieve. The pursuit of this idea had brought widespread poverty after the establishment of the People’s Republic, and there was no way to achieve prosperity for everyone. Finally I recalled the famine of the 1960s. Still until 1978 or 1979, people were terribly poor! For this kind of reasons I came to the conclusion that this communist theory was wrong. It was inconsistent with human nature and human society. People no longer had private property, because it was in the core of communist theory that private property was the root of all evil, and only by abolishing private property communism, equality without exploitation or oppression, and material abundance could be achieved. Making out more and more of the reality, and looking back on what had happened in the past, I began to completely abandon the theory of Marxism and the ideals of communism or socialism, and I began to see more and more of the historical facts. Looking back on the past, I realized that it was the one-party dictatorship of the Communists that has led to these outcomes.

When I arrived in prison, I started to think about a future political program and aim, and I began to advocate the abolishment of the one-party dictatorship in favor of a “Third Republic”. I supported a return to the legal system of the Republic of China. When Sun Yat-sen founded the Republic, he basically took a path of establishing freedom and democracy. Chiang Kai-shek followed this course, whether it was for resisting Japan or wiping out the Communists, it was all for this objective. I realized even more that communism was wrong, impossible to achieve, and fake.

Under the leadership of the Communist Party, a complete fiction was used to deceive people and the young generation. They were to accept these ideas as the best available, pursue them and work hard for them. If something felt bad, it just needed a little change, some different tone. But later I discovered that all this couldn’t be like that. Communism, when it combined with the Communist Party’s regime, was actually a very evil thing. It meant that no one could express differing views and opinions. Otherwise he would be imprisoned, tried and sent to a labor camp. Therefore, when communist thinking reached China and the world, it was an evil thinking that could not be changed or reformed.

Interviewer: How did you think about Mao Zedong at that time?

Xu: At that time, I had not arrived at completely repudiate Mao Zedong. I still thought that he had made his contribution towards China's independence and liberation. But then I realized more of the history. At the beginning I judged Mao like [early dissident] Huang Xiang: 30 percent negative, 70 percent positive. But later I reversed it to 70 percent negative and 30 percent positive. And again later, I thoroughly rejected Mao. But even evaluating Mao today, we should not praise him, but should not demonize him either. We should look at Mao more objectively. That is to say, we should not adopt a completely negative attitude towards some of the things he has done and achieved, because talking about historical figures, we have to see the historical situation and cannot just use today’s perspective. But in Chinese history, Mao’s society was authoritarian, and he brought authoritarianism to its peak.

Later, it became clearer to me that in past Chinese societies up to the Qing Dynasty, the bottom class in China had a certain degree of autonomy. China's rural areas were generally ruled jointly by the local gentry and wealthy families, and the government could not govern it brutally.

That was different under Mao Zedong. He infiltrated and regulated everyone’s life, whether it was in villages or institutions of ordinary people in cities. So the whole of China had changed... With its thousands of years of autocratic history, the Mao Zedong era was the most autocratic. And he also covered up many facts. He did not resist Japan during the Anti-Japanese War. He also committed many crimes when he ruled the country. He also hid the fact that China’s Gulag was just as cruel as the Soviet Gulag, and our "Gulag Archipelago" [title of a famous book by the Soviet writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn] was just as huge, as you can now see from "Jiabiangou" [a labor camp in Gansu Province, where 2,400 rightists were imprisoned in 1975; the writer Yang Xianhui wrote "Jiabiangou Chronicles" based on true stories from what was called China's "Gulag Archipelago".] Such books brought to light the persecution of intellectuals, dissidents and children of so-called reactionary families. What happened was very serious, but as student and people living in the cities, we were ignored much about these things.

Even when I later went to the countryside, the army and a factory, my knowledge remained very limited. I couldn’t possibly know all their crimes. That’s why my basic opinion on Mao was that he was the master of autocrats, and an incarnation of China’s evil over the decades he represented. In thousands of years of China's history, there has been no other autocrat like him, under whom so many people had to die abnormally. But I don’t want to blindly demonize Mao Zedong. What kind of person he was and how he performed, still needs to be looked at objectively.

Interviewer: But the question is, how did you discuss this issue with other democracy activists at the time, and how did you treat this issue? No doubt you debated whether China wanted socialism or not. What do you remember of these debates?

Xu: Yes, such discussions and debates happen in our editorial office. However, there were relatively few debates among our editors. We all had to go to our jobs, and I was personally very opposed to the idea of stopping regular work in order to engage in revolution like it had been during the Cultural Revolution. So I insisted that we attend our jobs every day. In addition, I only received a salary when I worked. Although my pay was very low, thirty-nine Yuan eighty [a month], without working I won’t have received it and I couldn’t have supported my family and the publications I run.