A Profound Political Turn - the End of the "Cultural Revolution"

Official Chinese historiography likes to call the era between 1966 and 1976 the "ten years of chaos", but it hardly ever mentions that it has been Mao Zedong himself who started this "Cultural Revolution" and encouraged physical violence against "class enemies", using these "struggles" to depose adversaries inside the Communist Party.

Yes, Mao probably did believe in his own revolutionary ideals, still his mass campaigns left millions of victims behind: intellectuals, artists and writers, teachers, common citizens, anti-communists as well as long-standing revolutionaries and Communist Party cadres. Many were deported to remote regions of China, others just fusilated and slain or tortured by the youthful "Red Guards".

Only calling in the soldiers of the "People's Liberation Army" against violent factions of the Red Guards and through the iron grip of the State and Party organs, it became possible to re-instate "order" throughout the country in the late 1960s. Shortly after, under the pragmatic Prime Minister Zhou Enlai, China manages to get rid of its self-chosen international isolation. In 1971 Beijing takes over China's seat in the UN from Taiwan, and in February 1972 US president Richard Nixon makes his stunning visit to Beijing to meet Mao and Zhou Enlai to put an end to decades of war-like confrontation.

1976 though becomes a year of profound political changes in China: In January the popular Prime Minister Zhou Enlai dies, in early April, the traditional day of the commemoration of the death ("Qingming") turns into hardly veiled protests against the radical Maoists in the leadership. They respond by deposing once again reformer Deng Xiaoping, who had been partially rehabilitated only in 1973 after severe persecution during the Cultural Revolution.

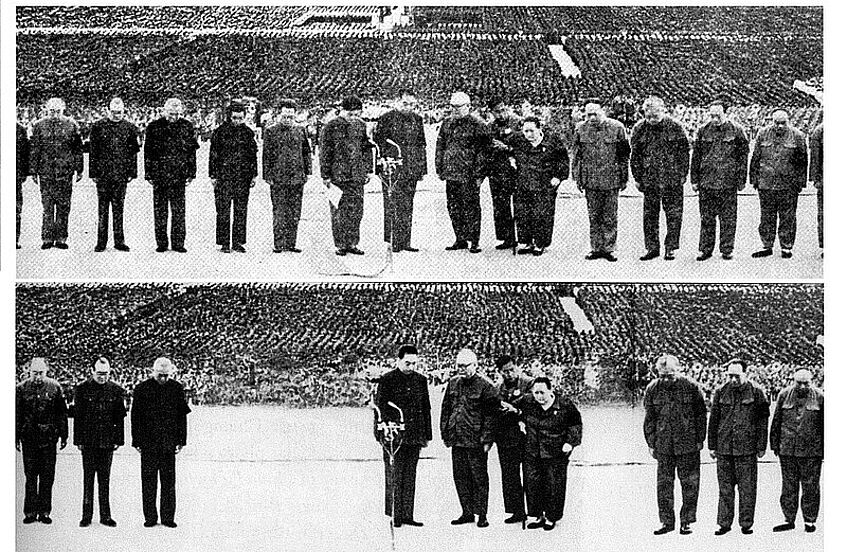

But on September 9, ailing Party Chairmen Mao Zedong also dies, and just four weeks later his closest collaboraters (now called the Gang of Four, including Mao's widow Jiang Qing) are arrested. It signals the beginning of the end of radical Maoism and the start of a new policy of "reform and opening" that should eventually completely change China's economic and political course.

The Gang of Four at Mao's funeral, photos have been retouched in later reports (two different issues of "China Pictorial", November 1976)

Protest against the System - Forerunners of the Democracy Movement

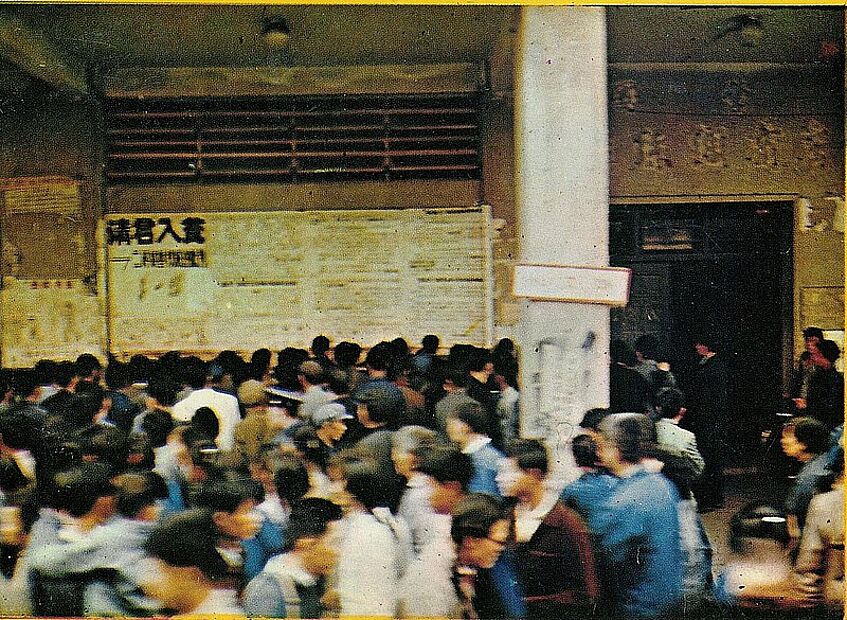

A big-character poster by "Li Yizhe" (Guangzhou, 1974)

Protest against the System - Forerunners of the Democracy Movement

Sporadic protests against corruption, political despotism and Mao's autocratic system already happen in the early 1970s. Some people who have badly suffered under the Cultural Revolution voice their grievances, former Red Guards feel a betrayal of "genuine socialism" and its principles of equality and respect of the will of the masses.

In Canton (Guangzhou, South China) in summer 1974 a citizens' group that uses the pseudonym "Li Yizhe" publishes a manifesto they call "On Democracy and Legality under Socialism" that becomes widely circulated all over China. In some other provinces, notably in Jiangsu and Zhejiang, we also see early protests against the excesses of the Cultural Revolution and Mao's autocratic regime. Criticism often formulated in so called "big-character posters" (dazibao) is usually quickly suppressed, and authors get harrassed and arrested.

Deng Xiaoping in Charge of Policies

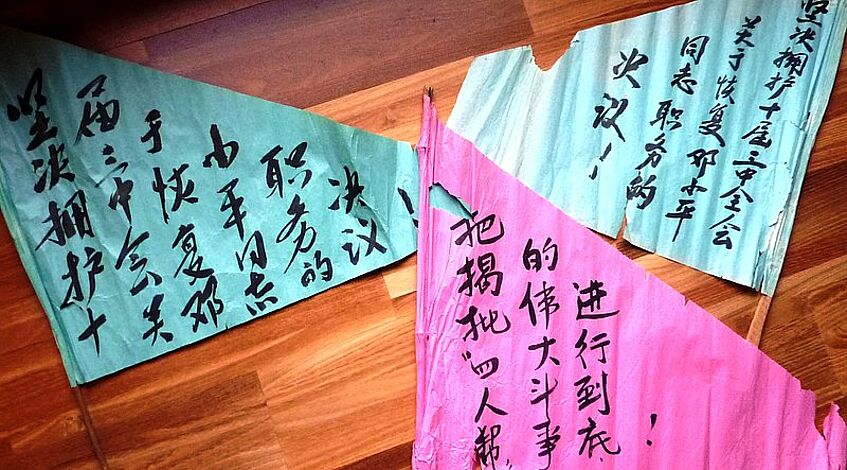

Slogans hail the dicision to allow Deng Xiaoping to return to the political leadership (Beijing, July 1977)

Deng Xiaoping in Charge of Policies

After Mao's death in 1976, Hua Guofeng who has been personally designated by Mao takes over the post of Party Chairman. But when Deng Xiaoping is allowed to return to politics in July 1977, he immediately becomes the powerful "grey eminence" of the Party, without ever formally holding the posts of Chairman of the CCP or Prime Minister. Many other politicians and high-ranking cadres who have been purged during the Cultural Revolution, are also rehabilitated during this period.

At a Central Committee conference in late 1978 ("Third Plenum of the Eleventh Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party") Deng Xiaoping initiates an ambitious reform agenda, focussing at first on an economic modernisation through market elements, more local responsibilities and an opening up towards global markets.

But there is also the idea to replace Maoist and Marxist dogmas by more pragmatic approaches in many other political domains. It should be successes that count, not political teachings, or as one of Deng's most famous sayings goes: "It doesn't matter whether a cat is white or black, as long as it catches mice."