The Chinese Democracy Movement in the International Media

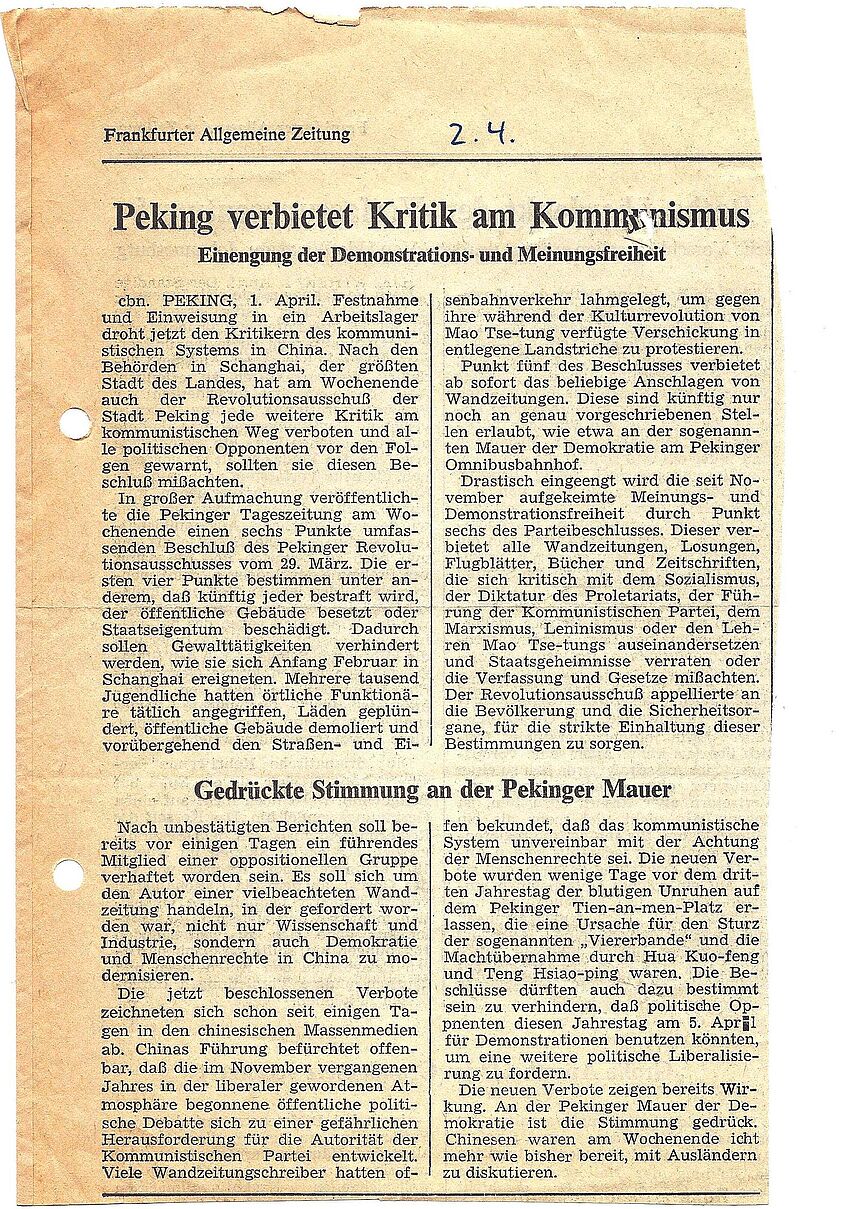

By a Correspondent of the "Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung", April 2, 1979

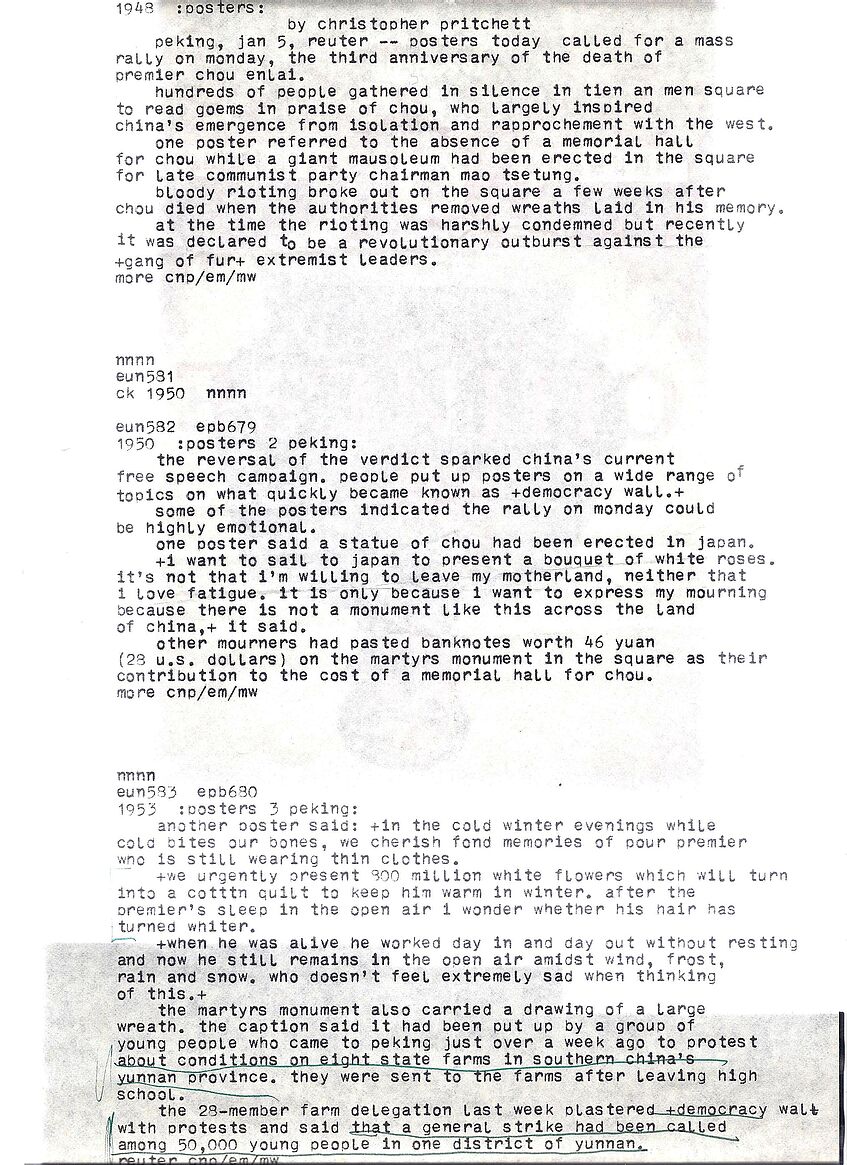

"Reuters", 5.1.1979 on a planned street march

From the beginning, international newspapers, political magazines, radio and TV stations (including those in Hong Kong) were highly interested in the big-character posters written by the Chinese dissidents, and in their independent journals demanding democracy, respect for human rights and a re-evaluation of the Mao era.

In 1978 there were still very few foreign correspondents accredited to Beijing, all together less than 50, and the majority of those still represented state and party media from other communist countries, more interested in intelligence work for their governments that in journalistic reporting for the public.

The big Western news agencies (Reuters, UPI, AP, AFP, ...) were present though, plus some leading newspapers from France, the United Kingdom, Japan or Germany. Canadian TV was the only Western TV station admitted then, up to the establishment of diplomatic relations (January 1979), US media could station their correspondents only in Hong Kong, with occasional chances to travel to the mainland.

When China started its policy of reform and opening, substantially more journalists got accredited to Beijing, and more of them understood and spoke Chinese. Personal contacts and journalistic investigations became much easier. Up to 1978 Chinese citizens still risked police interrogations and even arrest when they were caught in an unauthorized conversation or meeting with a foreigner.

With the profound political changes and the beginning of the "Beijing Spring", international media immediately started to focus on dissidents, on the new cultural expressions and the changes in daily life as well as the new thinking and personal aspirations of many Chinese.

From late 1978 and through early 1979, the agencies and big international newspapers reported almost daily (and quite extensively) from China, although much of this reporting remained superficial and focused on more sensational aspects, only few went more into depth or tried to interview the main actors of the movement in China. (For example, the leading activist Xu Wenli later remarked that his first longer conversation with a foreign journalist was his interview by author Helmut Opletal, as late as June 1979!)

Many Western media drew parallels with the dissident movements in the communist societies of Eastern Europe, especially with Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union. Another focus of the reporting were the repressive mesures taken by the Chinese leadership, such as arrests and court trials of prominent critics of the regime. And often the question was raised to which extent Western governments should (and could) try to influence these developments in China.

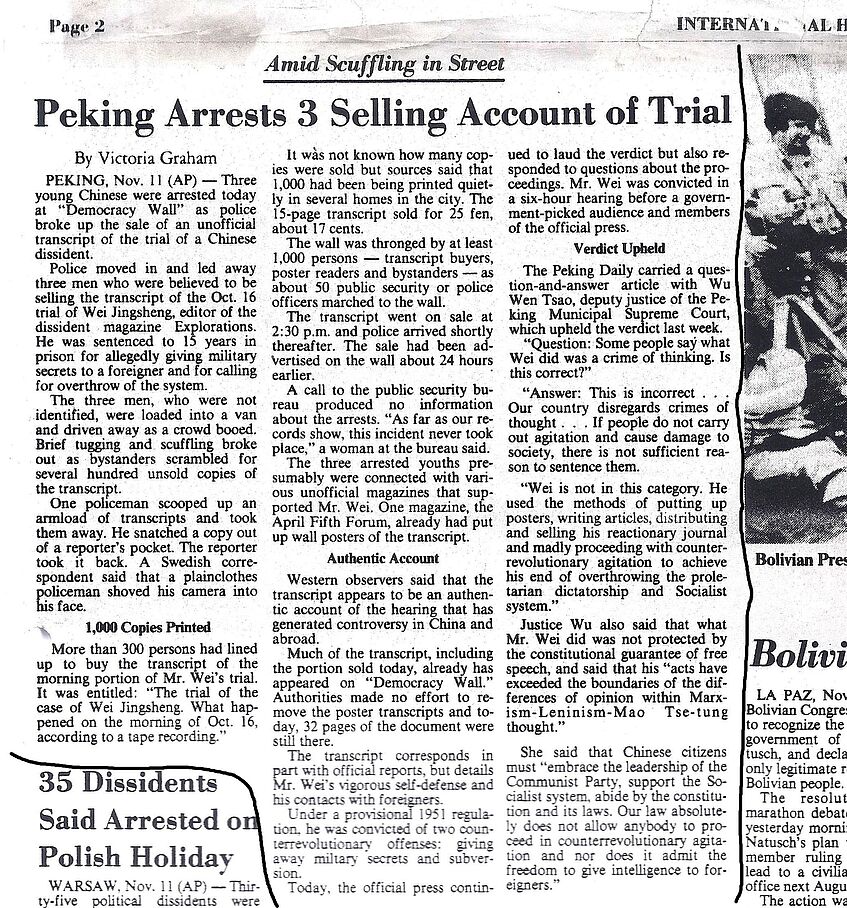

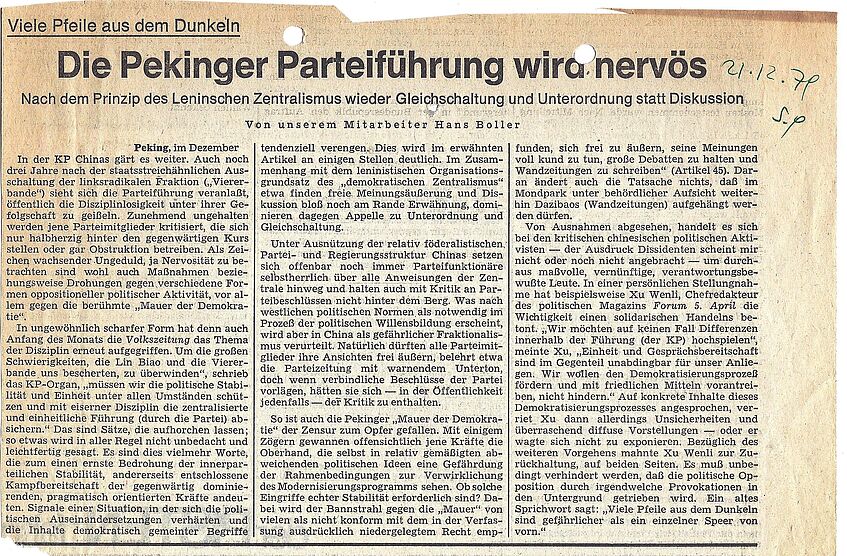

Above: "Süddeutsche Zeitung" (Munich), a political analysis by correspondent Hans Boller (21.12.1979) ----- Left: "International Herald Tribune", 12.11.1979, carrying an AP report by Victoria Graham, with a report on the arrest of Polish dissidents just below on the same page.

The influence of Western media

The Australian sinologist Andrew Chubb has described and analyzed the complicated relationship at that time between foreign journalists and Chinese civil rights activists in a dissertation called Foreign Correspondents & Democracy Wall: The impact of the Western media in China, 1978-1979. His main conclusion is that the foreign media and their representatives in Beijing did not just act as reporters, but they quickly became, at least indirectly, participants of the movement.

Chubb mentions several ways how Western journalists have influenced the movement, either through personal contacts or by their reporting: First, through discussions and conversations with Chinese dissidents, they increased their knowledge of political freedoms and democracy outside China; secondly, in some cases they gave direct material support by donations or by paying higher "subricription fees" for the journals, also by procuring material and equipment for them or handing publications otherwise not available in China to them. It is mentioned that in one instance an Amnesty International report on political imprisonment in China has been passed on, it was later quoted in one of the dissident journals. Thirdly, in at least one case, a foreign journalist established a channel of communication between the activists and the Chinese leadership, when the US columnist Robert Novak transmitted questions and demands from the Democracy Wall to paramount leader Deng Xiaoping and related Deng's answers back to the crowds at the Wall. And last but not least, many reports by foreign correspondents on the ideas and activities of the "Beijing Spring" were beamed back into China by Mandarin short-wave services like the VOA or BBC.

Andrew Chubb - who has mainly analyzed the big English language media - observes some very selective and one-sided reporting in the sample he studied. Many correspondents portrayed the "Beijing Spring" misleadingly as a mainly pro-Western movement that just wanted to copy the freedoms and democratic institutions from Europe and in the United States. The reports often emphasized exactly such aspects, while they ommitted for example the fact that a majority of the activists preferred to speak of "socialist" democracy. No wonder, says Chubb, that Wei Jingsheng, who attacked the Communist Party more than all the others, became the most quoted and revered of the dissidents, although he was rather considered by his fellow activists a marginal figure of the movement (p.44).

Another point made by Chubb is that the reporters from France, Britain or the US seemed to be more interested in power struggles within the leadership or in dazibaos attacking high-ranking politicians by name than in the substance of the political debates and personal motives of the activists. And often the correspondents misconceived the specifically Chinese backgrounds of the Beijing Spring that made it quite different from dissident movements in Eastern Europe.

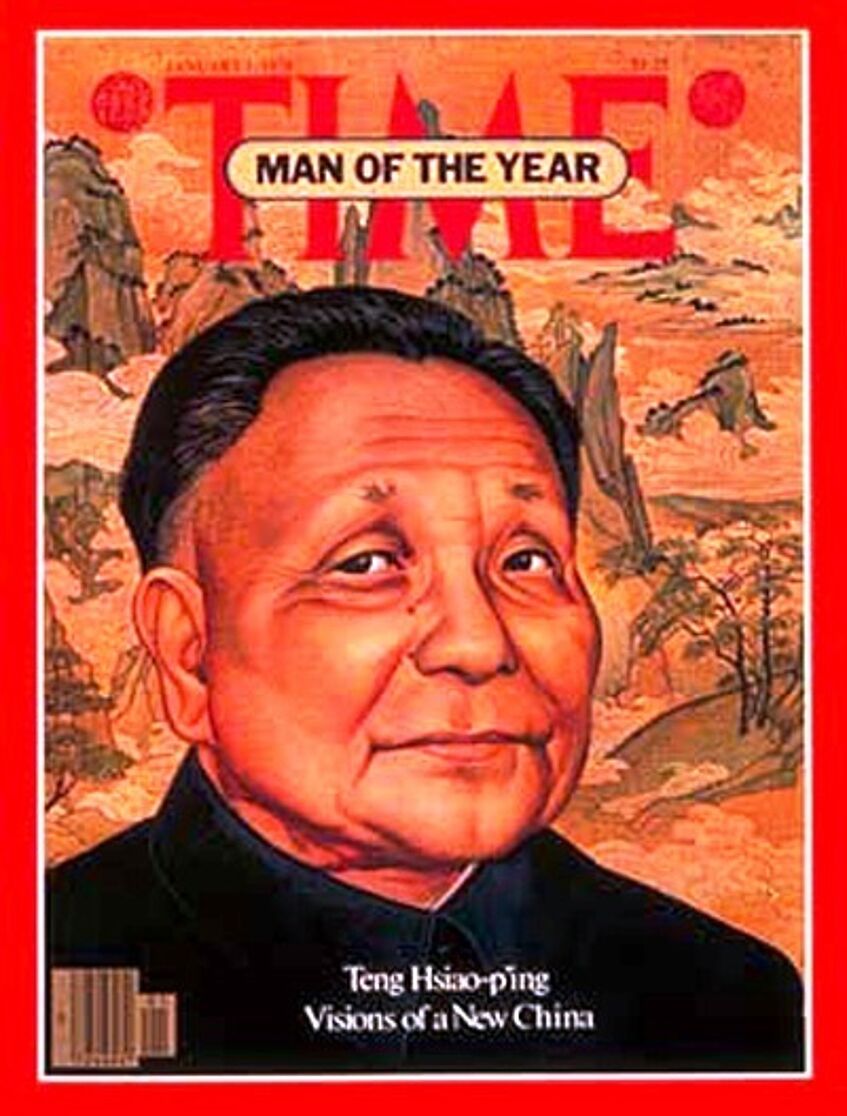

It is clear that both sides - rights activists and the Chinese leadership - have tried to use the international media for their advantage: The Democracy Wall campaigners hoped for - and eventually gained - moral and (occasionally) also material support. On the other side many Western media heaped excessive praise on Deng Xiaoping's leadership and greatly enhanced his international reputation. It was like this, that in the international public opinion, he became seen as the man who allowed open debates on democracy and freedom of expression, the man who promoted profound economic reforms, and also the man who contained the conservative Maoist faction within the Party, and thus profoundly changed China's course.

Hong Kong

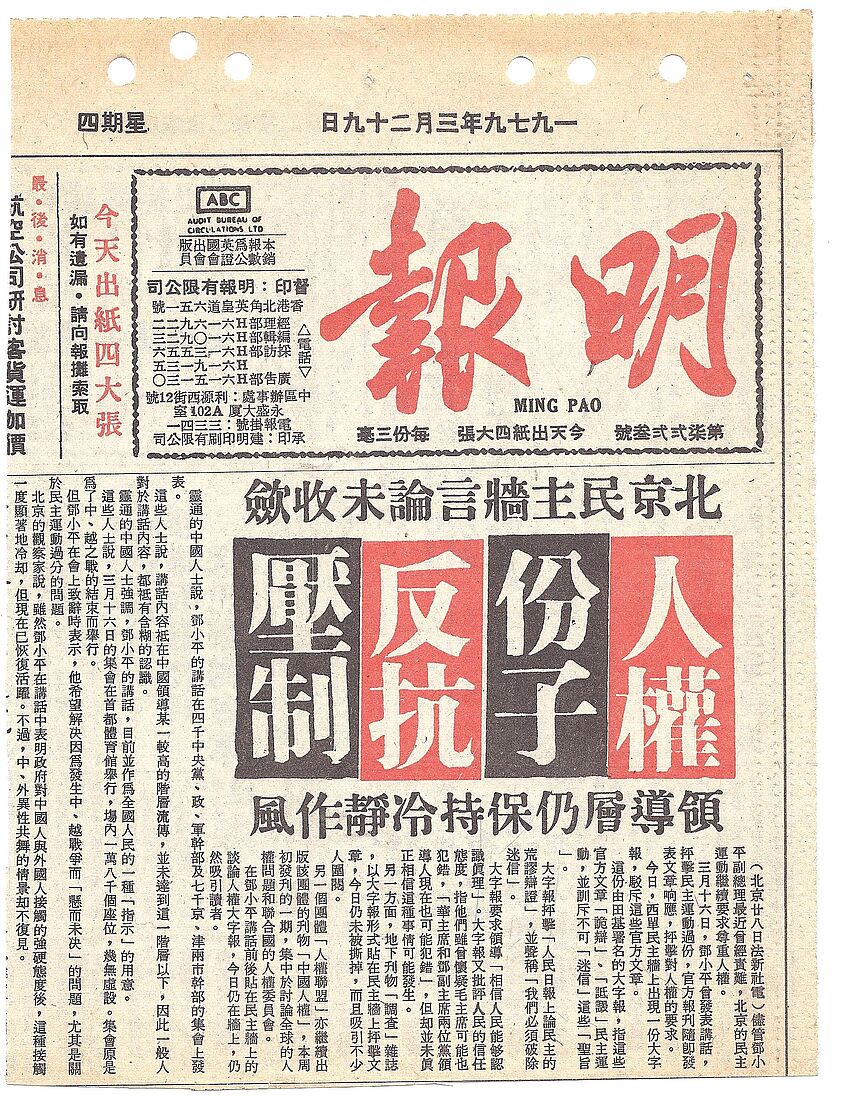

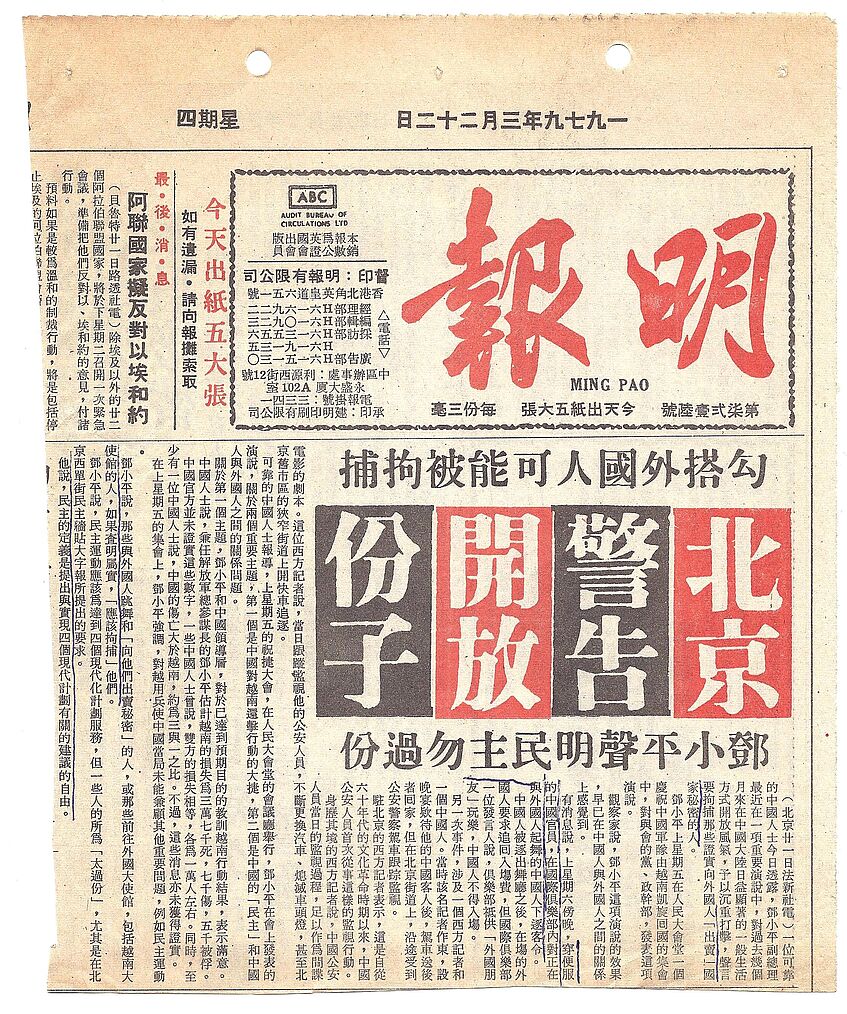

Particularly comprehensive reporting could be found in the Chinese language publications (and also some English language media) in the still British crown colony of Hong Kong. The big independent daily "Ming Pao" (明报) and several bi-weekly and monthly magazines had their own sources who constantly supplied them with photos, interviews and other information from Beijing, Shanghai or Guangzhou.

"Ming Pao" (Hong Kong), 29.3.1979, "Human Rights Activists Struggle against Repression"

"Ming Pao" (Hong Kong), 22.3.1979, "Deng Xiaoping Cautions against Extreme Democracy"

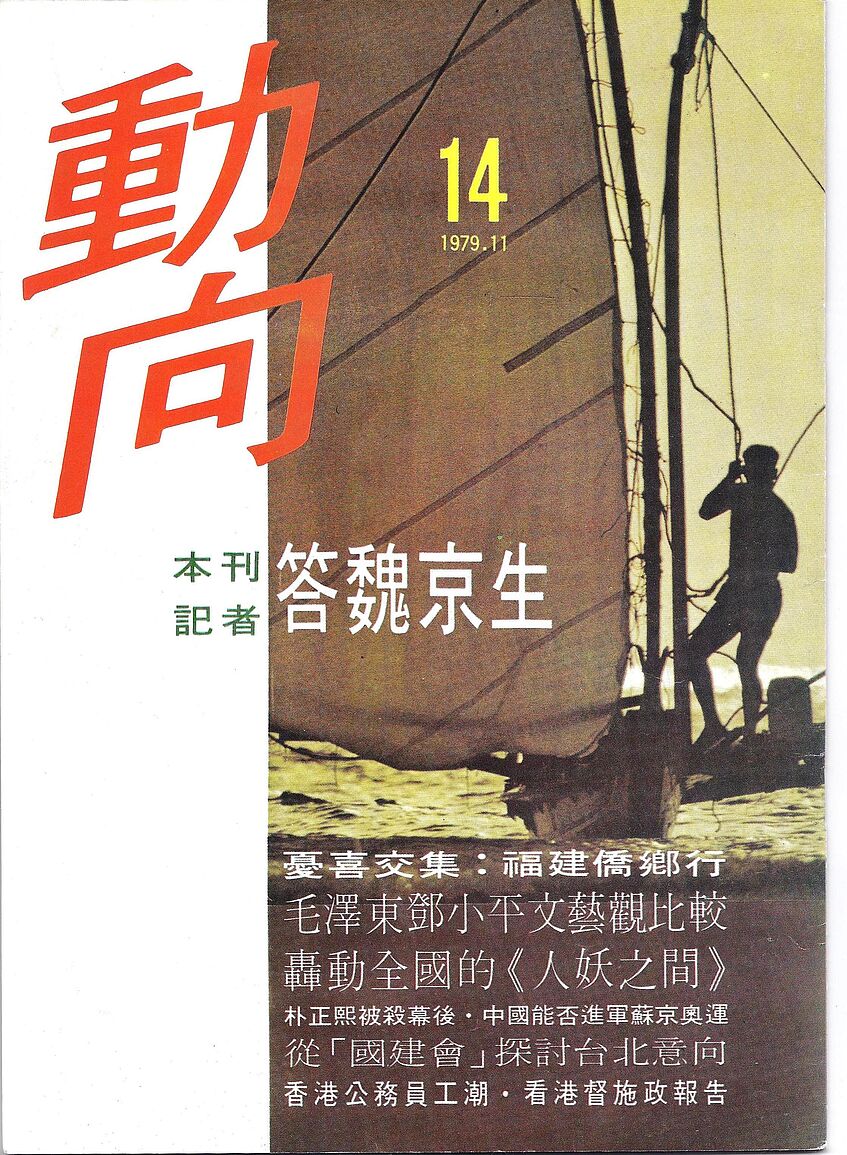

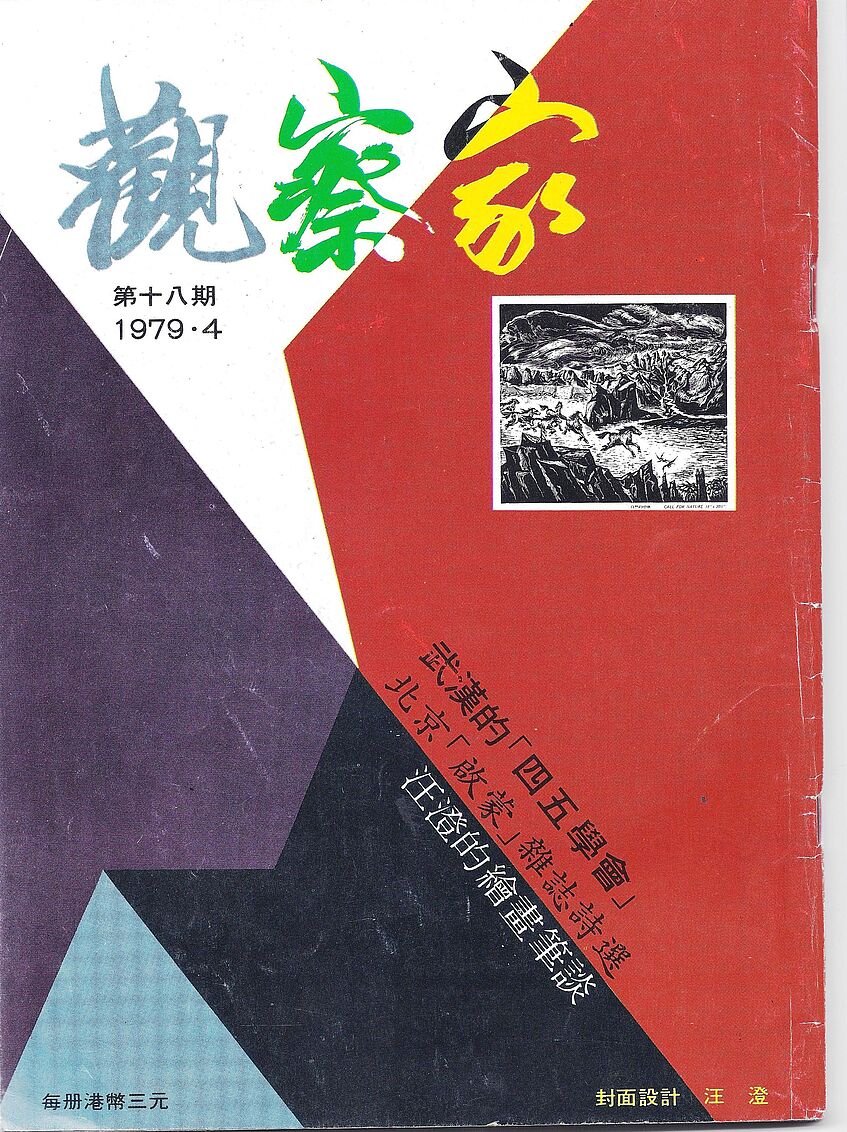

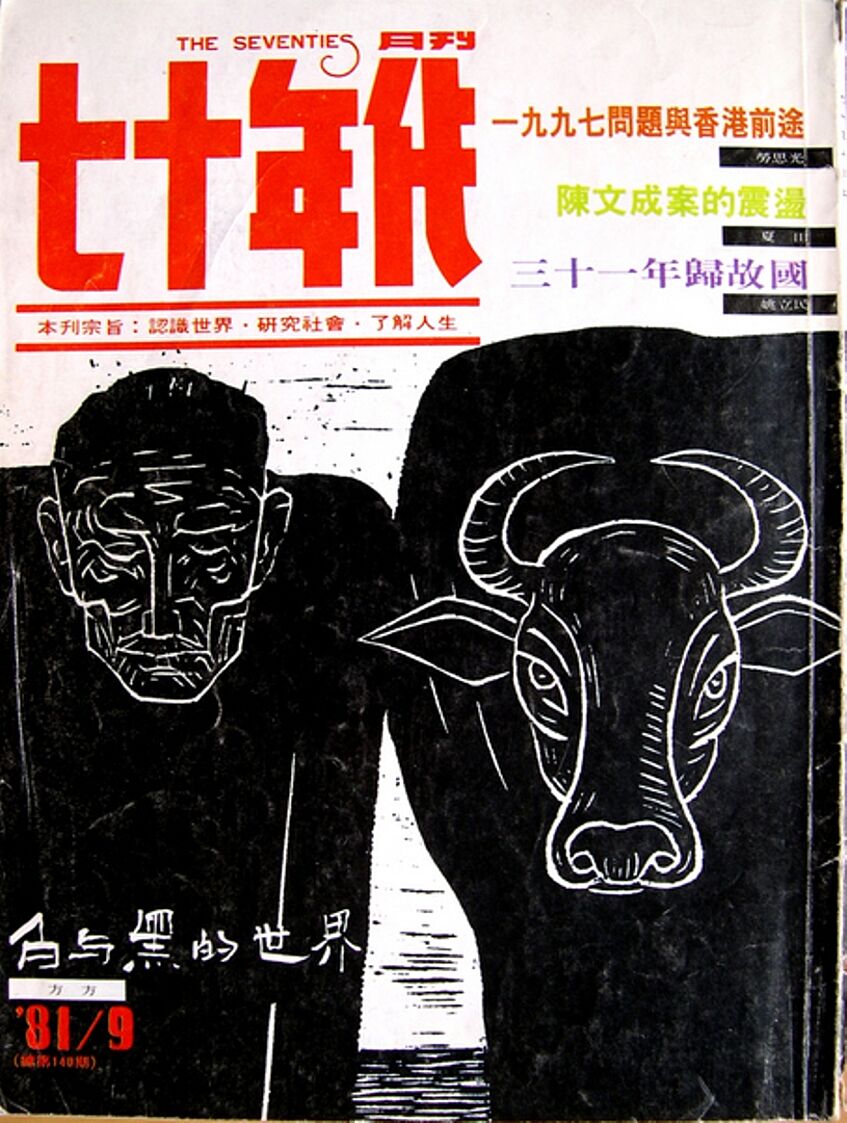

A number of these journals such as the "Observer" (Guanchajia 观察家), "Zhengming" (争鸣), "The Seventies" (七十年代) oder "Dongxiang" (动向) were even specialized in reporting political insider information and on social and cultural developments in mainland China.

"Dongxiang" (Hong Kong, 1979), with a debate on imprisoned dissident Wei Jingsheng.

"The Observer" (Guanchajia), Hong Kong, 1979, advertising on its cover a report on the Democracy Movement in the city of Wuhan, and details on the "Enlightenment Society".

"The Seventies" (Qishi Niandai), Hong Kong, 1981, carrying a wood-block print by Ma Desheng (from the 1980 "Stars" exhibition) on its cover front.

Already in the course of the year 1979, the interest of international media in the Chinese democracy movement began to subside, as economic developments and aspects of international relations became more important for the news.